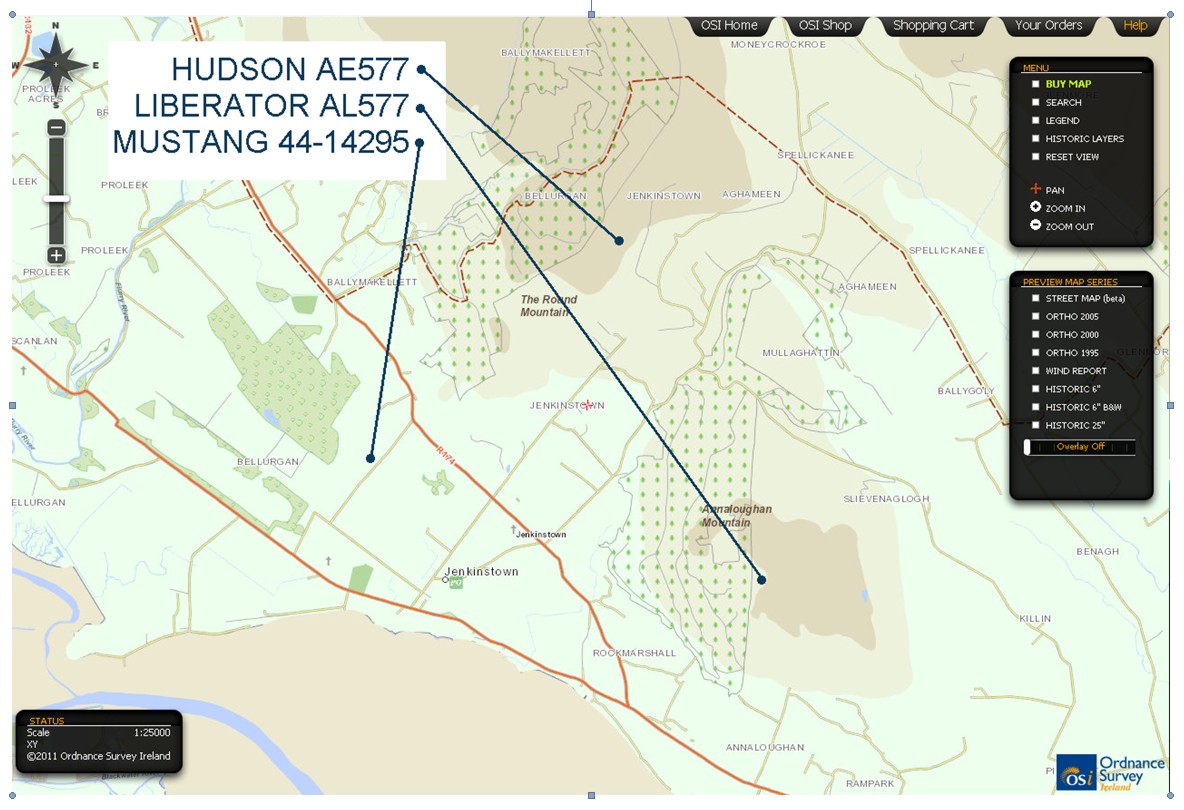

Consolidated Liberator, AL577, Jenkinstown, Co. Louth

In terms of

loss of life, the worst of the wartime air crashes occurred on

a lonely hill top in County Louth in early 1942. The 16th of

March, 1942 would see the deaths of fifteen young allied

airmen when their bomber crashed in to the mountain named

Slieve na Glogh, which rises up above the townland of

Jenkinstown on the Cooley Peninsula. It was the second of

three fatal wartime crashed in the area, the others being in

1941 and the last in 1944.

In terms of

loss of life, the worst of the wartime air crashes occurred on

a lonely hill top in County Louth in early 1942. The 16th of

March, 1942 would see the deaths of fifteen young allied

airmen when their bomber crashed in to the mountain named

Slieve na Glogh, which rises up above the townland of

Jenkinstown on the Cooley Peninsula. It was the second of

three fatal wartime crashed in the area, the others being in

1941 and the last in 1944.

This area would witness the destruction of three aircraft before the war ended. A British Hudson bomber crashed with three fatalities in 1941 and a P-51 Mustang fighter of the US Army Air Forces crashed in September 1944 killing its pilot.

The story of the aircraft crash has been told many times in a

number of publications and these are listed below.

This photo, posted on social media by a local man, was

apparently taken at the crash site and this is the best copy

available, a snap taken on mobile phone. The view was

explained by local man Derek Roddy as being to the west across

the crash site from Slievenaglogh. The slopes in the

background, Annaloughhan Mountain, are, in 2022, covered with

forestry but the stone wall is a common visible feature on

both. The tail fins of the aircraft appear to be about on

top of the remains of a low stone wall feature which runs

through the middle of the photo. It is along this wall

that the 2022 memorial is located.

A modern comparison would be the image below taken in May 2022.

The scene would appear to show the crumpled tail of a Liberator

bomber in the right center of the photo, with one of the rounded

tail planes still attached and visible. A comparison can

be made with this stock image of an early Liberator bomber.

A further set of photos, it seems known only in the local area

until 2022 show the terrible aftermath of the crash and are

testament to the violence of the minutes of Liberator

AL577. These are all copies of scans or photo copies that

Noel Roddy had collected and annotated over the years.

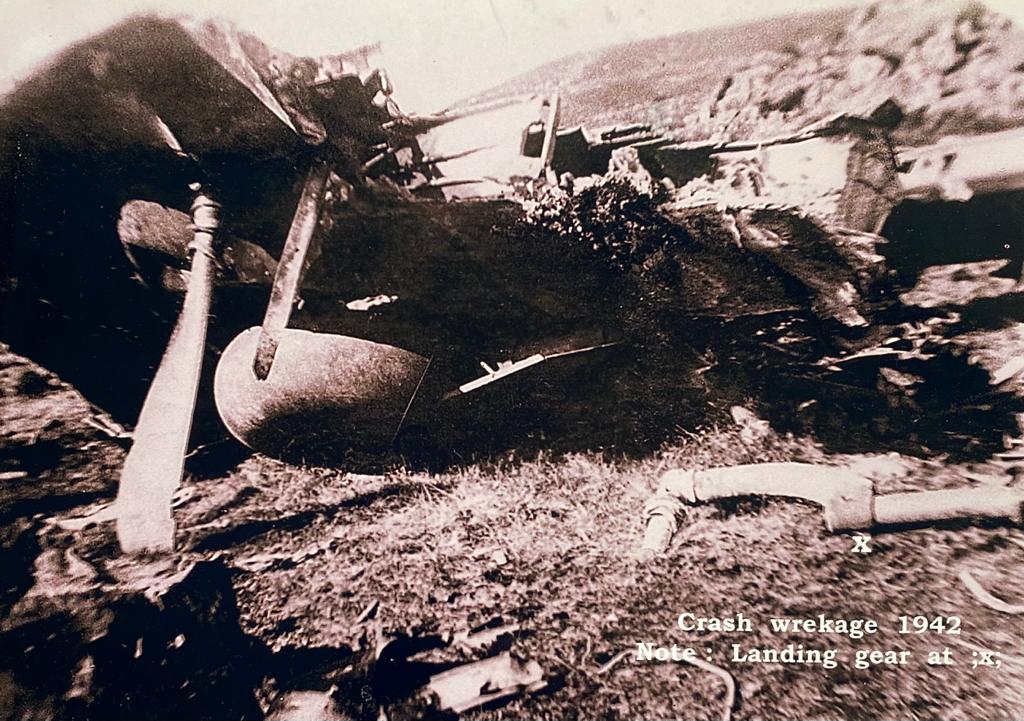

This photo shows wreckage with a landing gear tire and one

landing gear leg. The curved item to the left of the tire

appears to be a broken propeller.

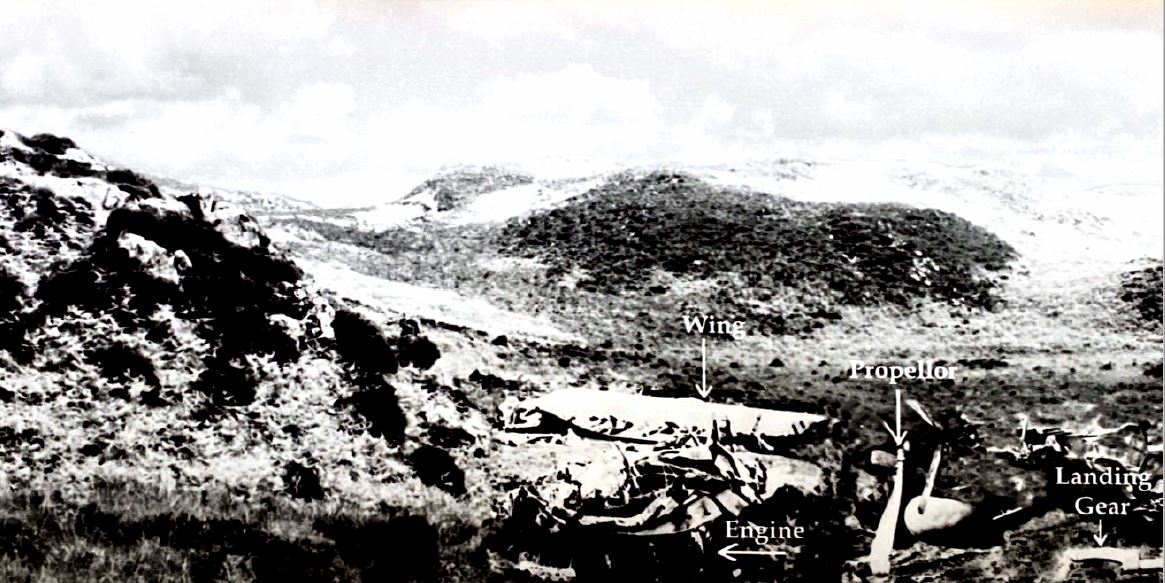

In the image below, the viewer is looking south east across the

crash site with a particular rocky outcrop on the left of the

image. Again, Noel Roddy has labeled the images.

The labeled wing above can be seen in the photo below.

The story of the crash began in the far away deserts of North

Africa in the winter of 1941/1942. During 1941, Royal Air Force

(RAF) 108 Squadron was engaged in bombing missions in support of

the British campaign in North Africa. In December 1941, it was

decided that in the coming months the unit would transition from

the Wellington twin engine bomber to the American built,

Consolidated Liberator. The process of transition is explained

in detail by Andreas Biermann in his 'Crusader

Project' Blog - The first B-24 Liberators in the Desert.

The 108 Squadron diary records the receipt of the first new

Liberator on the 29 Nov 1941 at Fayad. The serial number

is not recorded in the Summary (Form 540) and it is immediately

noted that the aircraft arrived without any form of defensive

gun armament or technical publications. The following 5

December, "The Liberator" is stated to be serviveable and the

training course began. The Details of Work (Form 541)

record this to be AL577, and it flew for the remainder of the

month under the command of Major Cairns, Lt Reynolds and

others, who were members of the US Army Air Forces carrying out

conversion training for the Squadron. Deliveries of

further aircraft are recorded on 9 December, 10 December and 13

December. Again their serials are not recorded but AL574

appears in the Form 541 on the 13th and AL530 on the 19th.

The fourth aircraft was AL566 which went direct to a Maintenance

Unit for fitment of armament. AL577 flew its first bombing

practice flight on 30 December 1941. Upon arrival at the

squadron, the aircraft were assigned an individual aircraft

letter which was painted in large letters aft of the roundel on

the fuselage.

Through out the most of January 1942, AL577 continued to carry

on the training role in the squadron's effort to become fully

serviceable on the type.

Finally, on the night of January 29th, AL577 flew its first

bombing raid, to El Aghelia returning the following afternoon to

the more mundane training role. The Form 540 details

Liberator 'O' being flown by F/Lt Alexander to attack motor

transport on the Agedabia - Aghelia road. Little mention

of AL577 is found in February until the 16th February when it

flew a raid on Benghazi. It again is not mentioned until

21st, 23rd and 27th February when it flew local air tests close

to the base. It might be the case that the unit was no

longer recording all training flights. The identity letter

O is associated with AL574 in February records.

The 1st of March records AL577 being fitted with twin 0.5"

Browning machine guns but noting this was still inadequate.

The aircraft, AL577, this time noted as being aircraft ID

letter N, carried out a special duties flight on the 2 March

1942 to the occupied island of Crete.

Following this introduction into service it was decided that the entire Squadron should convert to the Liberator and it was decided that one of the new aircraft would fly to the United Kingdom with a cadre of experienced 108 Squadron members. There they would collect and prepare new Liberator bombers for ferry to North Africa. This decision is mentioned in the 28 February 1942 ORB. Ahead lay a long and dangerous flight from Egypt, across North Africa to Gibraltar followed by the long over-water flight to England across the Atlantic. As squadron veteran Steve Challen explained in his writings, the Squadron leader and squadron gunnery officers both volunteered to take one of the bombers to England. On board the aircraft were a crew of six men with thirteen more members of the squadron as passengers. These included six pilots, three navigators, three wireless operator/air gunners (W.Op/A.G) and one fitter mechanic. The nineteen men were a mix of English, Scottish, Australian, Canadian and a lone Kiwi.

Sources for research on this crash are many. Primary among

these are the Irish Army Military Archives report dating from

March 1942. The Australian National Archives also have Casualty

files for three of the Australians on board the aircraft. From

one of these files comes this text describing the outline

circumstances of the crash. And the UK national Archives hold

the AIR81/12771 casualty file for the men of AL577. In

that is a four page report from RAF Northern Ireland

Headquarters dated 25th March 1942 and detailing the events of

the preceding days, the disposition of the dead and wounded and

burial of the wounded in Belfast on the 21st of March.

REPORT ON FLYING ACCIDENT -

LIBERATOR A.L. 577 - 16th March, 1942.

From the information available and action taken at this

Headquarters, the following report is submitted on the above

accident :-

1. The aircraft, LIBERATOR A.L.577, belonging to No. 108

Squadron, Headquarters, Middle East, took off from Egypt on

15-3-42 in transit to the United Kingdom, intending to land

at R.A.F. Station, Hurn, near Christchurch, Bournemouth,

lost its bearings and crashed near Jenkinstown, Dundalk,

Eire, (map reference IJ.1408) at approximately 14.10 hours

on 16.3.42. It is understood from Accidents, Gloucester,

that during the early part of the flight the aircraft

acknowledged orders to return to Egypt owing to the bad

weather conditions prevailing over the British Isles at that time. The

aircraft was West of its course and crashed into high ground. As the accident occurred in Eire and

the evidence available suggested that the cause was due to

disobedience of orders and bad navigation, it was considered

by Accidents, Gloucester, that no useful purpose would be

served by ordering an investigation.

There were 19 occupants in the aircraft, the particulars of whom have now

been confirmed by a survivor. As a result

of the accident, 15 were killed and 4 injured.

2. The injured were admitted to Dundalk Hospital, Eire, and

as their progress permitted, they were transferred over the

Eire border to Daisy Hill Hospital, Newry, and those whose

condition permitted of further travel, were eventually

conveyed to Stranmillis Military Hospital, Belfast,

Arrangements were made for the conveyance of all the

deceased from the scene of the accident to the mortuary at

Messrs. Melville & Co., Funeral Furnishers, Townsend

Street, Belfast. Full details and a summary of the action

taken are given below:-

The report concluded with the following description of the

funeral:

A mass funeral of the under-mentioned took place on

Saturday, 21st March, 1942, from the mortuary at Messrs.

Melville & Co., Townsend Street, Belfast, for interment

in the Belfast City Cemetery, and Service honours were

accorded ;-

F/Lt. Francis Charles BARRATT, D.F.C. (77959).

Crew.

R.62738 F/Sgt. GOODENOUGH, Carlton Stokes.

Passenger.

R.63939 Sgt. KING, Beorge Frederick.

Passenger.

Aus. 402677 Sgt. SLOMAN, Herbert William Thornley.

Passenger.

Pilot at time of Crash - Aus. 402429 Sgt.

WILLIAMS, Lindsay Ross.

4. W/Cdr. R.G.E. Catt, Officer Commanding, R.A.F. Station,

Belfast, was in charge of the funeral party which comprised

4 Officers, one Warrant Officer, 5 senior N.C.Os. and 56

airmen acted as pall bearers.

5. The funeral cortege moved off from Messrs. Melville at

15.00 hours and the 5 coffins draped with the Union Jacks,

were borne by the pall bearers. The cortege was

received at the gates of the City Cemetery by W/Cdr. P.

Murgatroyd, representing the Air Officer Commanding, Royal

Air Force in Northern Ireland, the Reverend W. E. Woosnam

Jones, and the Reverend W.Chestnutt,M.A., the officiating

chaplains. At the conclusion of the

burial service, the last post was sounded,

The history of the flight and crash of AL577 was researched

after the war by a former comrade of the men, Steve Challen, who

as F/Sgt Grenfell Stephen William Challen 937815, flew with many

of the men who came down on AL577 in Louth. Steve Challen died

in 2004 but not before he attempted to contact the survivors of

the crash, T E 'Pat' Pattison, S F Hayden and J R Anderson. He

also contacted many of the relatives of the dead men, including

the sister of Paul Morey who provided copies of the information

Steve had collected. Steve Challen wrote an article about the

brief use of Liberators by 108 Squadron in Flypast magazine in

1998. In this he reported:

worsening weather en route. It was

estimated that they were approaching the point of

no return. Coupled with this news, the Bendix radio

was reported unserviceable — despite the efforts of all the

wireless operators on board they were unable to find the

fault. Sgt Gibbons had the most Bendix experience — having

gained it on the Sumatra trip. While attempts were in hand

to restore communications, discussions took place on the

flight deck on whether or not to continue. The consensus of

opinion, including that of the passengers, was to fly

on.

Much later they found themselves above 10/10 cloud

which continued long past their ETA (estimated time of

arrival) at Hurn in Dorset. Everyone was warned to

prepare for a possible ditching. Descending slowly through

the cloud, a glow was seen which could only be the lights of

a town or city in neutral Eire. The size and brightness of

this illumination convinced WgCdr Wells that It was Dublin.

Rather than risk internment in Eire, he altered course for

Aldergrove in Northern Ireland, failing to allow for high

ground on their track. The fuel situation was now becoming

serious.

Articles were written about the crash by Lt Col N C

Harrington, Irish Army, Michael O'Reilly from Meath, Tony Kearns

of Dublin, Patrick Cummins of Waterford and also appeared in

books by John Quinn and David Earl.

The late Irish researcher Tony Kearns summarized the aircraft

movements over the east coast as recorded by the Irish

Army: The Liberator appears to

have crossed the coast at Dublin where it first observed

lights. The military post at the Bull Wall reported an

aircraft at 0630 hrs. moving northeast. It passed over

Sutton less than a minute later. The search-light post at

Howth also reported the aircraft, but its course was

uncertain due to the strong winds. After heading up

the coast to Donabate its track was lost at this time

and no more observations were made until 0735 when it was

reported over the military post at Dundalk. The weather that

morning was overcast with poor visibility and strong

southerly winds making it difficult to even hear the

aircraft from some of the observation locations.

First hand testimony of the flights events survive from at

least two of the survivors, from letters they wrote to the next

of kin of their comrades and later after the war to Mr. Challen.

Sgt Pattison wrote to tell the father of Sgt. Morey:

We left Egypt on March 15th in a

Liberator (giant American four engined bomber); there were

nineteen of us together with full kit on board.

Our mission to England was a special one, we were not

coming back to stay. The nineteen fellows consisted of the

ships crew of which your son was navigator and three

specially selected crews, with one flight engineer. We left

Egypt at 5p.m. (Egyptian time) and had a wonderful trip

across the Mediterranean and France; all this time we were

right on course. The first indication of trouble was shortly

after we flew over the French coast, heading for England. We

ran into the worst weather I have ever experienced in three

years of flying. It was almost impossible to see out own

wing tips. We all knew we should require a good deal of

wireless assistance if we hoped to get down safely. Then the

real trouble began - the Wireless Operator could not contact

any station in England because of some fault in the wireless

equipment due to weather conditions. We knew we were over

England and we lost height to two thousand feet in order to

enable us to pin-point our exact position, but the weather

was just as bad at two thousand feet.

It would have been unwise to do down any further

because of barrage balloons or mountains so we climbed up

again and cruised around hoping for the weather to clear,

but it did not; instead it became even worse. By this time

we had been in the air over fifteen hours and we were

carrying fuel for just over fifteen and half hours. We were

preparing to bale out and chance it but before we could do

so someone spotted lights on the ground. The captain

immediately dived down over the lights which we knew was

Dublin and circled around at above five hundred feet. About

this time two of our four engines ceased running and we were

unable to climb very well. The captain then headed straight

along the coast of Eire to try to land at an aerodrome in

North Ireland. We had been flying for about half an hour

after leaving the lights and all this time we were gradually

losing height. There was a terrific crash and when I awoke I

found myself lying about twenty yards from the machine,

which by this time was practically burned out. I tried to

stand up, but couldn’t, as I found later in hospital I had

fractured my spine in two places. I managed to crawl around

in a sort of daze and soon saw there was not much I could do

for any of the other chaps in my condition. So I crawled

over the mountainside to look for help, but there was no one

in sight, I started to crawl back to the machine but fell

unconscious before I got there. I woke up while being

carried down the mountain on a stretcher and found that we

were not discovered until three hours had elapsed.

Written from Majestic Hotel, No. 7 P.R.C.,

R.A.F., Harrogate, Yorks, 5th June 1942

The RAF Casualty file for this crash held in the UK National

Archives, AIR81/12771 contains much correspondence between the

families and the authorities. The letters from parents in

the UK show their sadness having learned their sons died in

Ireland when they understood them to be in Egypt. They

were hours away from possible home leave visits.

The remaining personnel of 108 Squadron still in Egypt were

understandably shocked to learn of the crash and deaths of so

many of their friends and colleagues. The Squadron ORB

contained the following entry for the 17th of March 1942:

It is with deep regret

that this Squadron records that the Liberator, captained by

W/Cdr. Wells DFC., carrying crews home for the Liberator

Ferry Flight, crashed

in Ireland - this was a great blow indeed to the

Squadron. It has since been learned that out of the nineteen

personnel (including five officers) that F/O J. R. Anderson

DFC., and Sgts. Amos, Pattison and Hayden were injured, and

the remainder killed. - The Squadron could ill-afford to

lose these valuable crews.

Wing Commander R.J. Wells DFC. by his

splendid leadership, enthusiasm and zest for operations

built up for this Squadron a worthy reputation. It was his

ambition to have the Squadron re-equipped with Liberators

and it was with this end in view that he proceeded to U.K.

All who knew him were impressed by his remarkable courage,

his sense of justice and his interest in the welfare of all

ranks. His personality and high spirits made him a favourite

with all - his loss is deeply felt.

F/Lt. F. C. Barrett DFC., P/O J.P. Tolson and P/O

W.B. Stephens were all Officers with a keen

sense of duty; at all times their work in the Squadron being

of a

exceptionally high standard.

It is a complete mystery to all as to how

this crash occurred as both the Captain and crew had a wide

extensive and varied experience.

ratidn

From various sources the following collection of photos has been assembled of the men on board AL577. Some have come from family members, some from publications and others from online sources.

|

(Snipped from IWM photo CM 2380) |

|

|

|

|

|

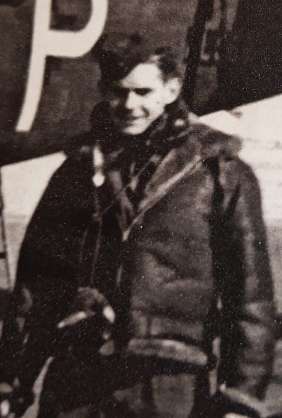

F/Lt (Air Gnr) Francis Charles BARRETT DFC 77959 + |

F/O (Pilot) James Robert ANDERSON DFC 79508 |

|

|

|

P/O (Pilot) Wilfred Bertrand STEPHENS 113267 + |

Sgt (WOP/Air Gnr) Thomas Edward PATTISON 644625 |

Sgt (WOP/Air Gnr) Sydney Frederick HAYDEN 910905 |

Sgt (Fitter 2E) Andrew McMillan Smith BROWNLIE 546659 + |

Sgt (WOP/Air Gnr) Walter Paul BROOKS 931402 + |

F/Sgt (Pilot) George BUCHANAN 1060536 + |

F/Sgt (Obs/Nav) Carlton Stokes GOODENOUGH R/62738 + RCAF |

F/Sgt (Obs/Nav) Leslie George JORDAN 905148 + |

P/O (Obs/Nav) George Frederick KING J/15525 RCAF + |

F/Sgt (Pilot) Herbert William Thornley SLOMAN 402677 + RAAF |

- |

Jim Anderson the son of J R Anderson was so kind to send on many photos from his fathers collection including this one below of a 108 Squadron football team.

J R Anderson is seated in the middle of the of the above group, his pilot's wings badge visible on his chest, and the DFC award below that. James Anderson came from New Zealand and had trained with the Royal New Zealand Air Force prior to transferring to the RAF. He began his wartime career with 40 Squadron of the RAF, piloting Wellington bombers on raids against targets in Germany and France.

A group photo from Jim Anderson of 108 Squadron airmen, without names recorded. The grandson of the airman on the extreme right of the photo recognized his grandfather, David Fairclough Smith.

The above photos was supplied by the Anderson and Brooks family and is described as a press photo of 108 Squadron. Identified in this are Walther Brooks standing at the left, wearing shorts and with flight jacket open. Kneeling on the ground in front of him appears to be F C Barrett based on other photos received of him. Compared to the photos that the Pattison family sent, T E Pattison seems to be the sixth airman from the right kneeling.

The remains of the dead airmen were returned to their families

for burial with the exception of the Australian and Canadian

airmen. They were buried in adjacent graves in Belfast City

Cemetery on 21 March 1942.

Richard John Wells was a 28 year old combat experienced

pilot. Son of Richard Alexander and Ada Wells, he was born in

1913 in Yarmouth, Norfolk. His wartime records show

his fathers address to be 48 Mere Street, Diss in Norfolk and

his mother at addresses in Romford, Essex. He had been

commissioned as an RAF officer in 1937 and was posted to the

Middle East. His service career saw him twice awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross in 1941, first with 148 Squadron and

later with 108 Squadron. Essex newspapers reported in 1941

and 1942 that his parents in Romford and he had attended Beccles

College.

Richard's cousin, Lt(A) Claude G H Richardson, a pilot in the

Royal Navy, Fleet Air Arm, was killed in a Supermarine Walrus

crash in January 1944 in Trinidad and Tobago.

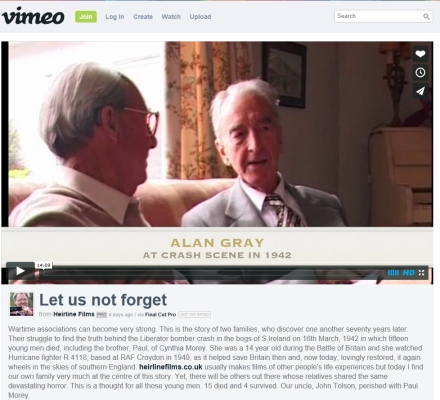

John Tolson came from Harpenden in Hertfordshire. Aged

just 21, he was co-pilot on this flight. John's father died only

a year after him and both son and father lie side by side in

adjacent graves. John's brother and family members came to

County Louth in 2002 and met some former members of the Irish

Army who had attended the crash site, along with local witnesses

and some who were raising a memorial to the lost crew men.

Members of John's family have been active in remembering John's

service and death. This short documentary was created by his

nephew to tell the story of John, Paul Morey and commemoration

efforts in Louth.

Let us not

forget from Heirline

Films on Vimeo.

Let us not

forget from Heirline

Films on Vimeo.

John's relative returned again in 2022 to view the new memorial

raised at the site.

Paul H

Morey was a 22 year old navigator from Leamington Spa. His

sister Cynthia wrote a book about her family and the death of

her older brother. That book included some of the details she

had obtained from Steve Challen in the 1990's. The book is

titled - 'Dark is the Dawn' and was published in 2009. T

E Pattison one of the survivors wrote to Paul's father after the

crash to tell what had happened and to pass on his memories of

Paul. Similarly the new commander of 108 Squadron also wrote to

the family to tell of his devotion to service and skills.

Paul H

Morey was a 22 year old navigator from Leamington Spa. His

sister Cynthia wrote a book about her family and the death of

her older brother. That book included some of the details she

had obtained from Steve Challen in the 1990's. The book is

titled - 'Dark is the Dawn' and was published in 2009. T

E Pattison one of the survivors wrote to Paul's father after the

crash to tell what had happened and to pass on his memories of

Paul. Similarly the new commander of 108 Squadron also wrote to

the family to tell of his devotion to service and skills.

Henry James Gibbons was the son of Herbert F. J. Gibbons

and Lilian E. Gibbons, of 9 Coleridge Road, Newport, just 20

years old at the time of his death. The 1939 register

finds him living at the above address with his parents and

employed as a railway clerk in the Docks Section. His

father also worked on the railways, as a freight train

controller.

He was an air gunner and wireless operator from the squadron.

In correspondence with former residents of his parents home, it

was learned that Henry was an only child and his photo rested on

the mantle of his parents house until their deaths, both in

1968, within a month of one another. No relatives were found in

the Newport area and it appears that his father, a railway

clerk, was born in Gloucester.

His name is recorded on war memorials in his native Newport, but

beyond that, little remains of Henry's memory it seems.

Charles Joseph Ingram was buried in West Ham cemetery

in London. His CWGC entry contains no next of kin details but

his death registration in Ireland gives his age as 24 years and

there is a corresponding birth registered in West Ham district

in 1918. His parents, Agnes and Charles W Ingram had married in

1914 and in 1942 lived at 10 Lincoln Road in Plaistow. The photo

of Charles above is a cropped image from the WW2

images collection. Charles is found on the 1939

register living with his parents and two sisters at Trinity St,

West Ham. He lists an occupation of Chartered Patents

Agents Clerk.

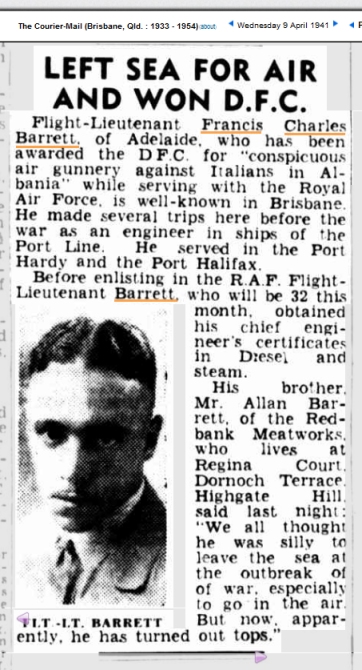

"Francis

C Barrett was a an Australian born officer serving in the

Royal Air Force. Son of Alice Ida and Francis James Barrett from

South Australia, Francis had been awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross in April 1941 for his service with 70 Squadron.

This squadron had served in the Middle East from the very start

of the war. Australian newspapers carried the story behind the

awards, his conspicuous service during 1941 including over

Albania. The Advertiser of Adelaide, published:

"Francis

C Barrett was a an Australian born officer serving in the

Royal Air Force. Son of Alice Ida and Francis James Barrett from

South Australia, Francis had been awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross in April 1941 for his service with 70 Squadron.

This squadron had served in the Middle East from the very start

of the war. Australian newspapers carried the story behind the

awards, his conspicuous service during 1941 including over

Albania. The Advertiser of Adelaide, published:

Flight-Lieutenant Barrett is the senior air gunner of the

R.A.F. squadron serving with the Near East Command. He has

earned a reputation as a first-class shot, and instructor. he

took part in a successful daylight bombing raid over Vlona,

Albania and it was chiefly due to his firing accuracy that

attacking Italian aircraft were driven off. One enemy plane

engaged in a counter attack was shot down by Flight-Lieutenant

Barrett.

Being an Australian meant that F/Lt Barrett was interred in the

Cemetery in Belfast with the other four overseas airmen. The

Barrett family would suffer further during the war as his

brother Allen Bernard was also killed in 1945 with Bomber

Command. He is buried in Germany. The men's mother had passed

away before the war in 1925. The newspaper article at left was

published with photo in the The Courier-Mail in Brisbane in

April 1941. In March 1942, South Australian newspaper carried a

memoriam notice for Francis apparently from a fiancee named

Nancy. Another March article published:

Mr. and Mrs. W. Beames, of Main avenue,

Frewville, have been informed that their nephew,

Flight-Lieut. F. C. Barrett, DFC, was killed on March 16

while on a transit flight in Jenkinstown, Kilkeney, Eire. He

joined the RAF in England, and was awarded for the DFC for

exceptional accuracy and daring in shooting down Italian

planes in Albania. Flight-Lieutenant Barrett attended

Pulteney Grammar School, and served an apprenticeship with

Herron Engineering. Co. Later he was an engineer at sea,

before joining the RAF. He was 32.

James Anderson was born in Lyttelton, New Zealand. His

father passed away when he was young. Finishing school he first

worked as an Electrical Fitter in the Electrical Supply

Department and later the Public Works Department in Addington.

He enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force in October 1939

and after graduating was posted to the United Kingdom and

received a commission in the Royal Air Force. Joining the RAF's

103 Squadron he piloted Wellington bombers on the early raids

against targets in France and Germany. His earliest combat

missions were two on the single engined Battle bomber during

September 1940 followed by raids as second pilot of Wellingtons.

In April of 1941 he became the captain of his own aircraft in

raids against the French port of Brest in the RAF's efforts to

destroy the German warships the the Scharnhorst and Gneisenhau.

It was for his actions during another raid on Brest on June

13/14th 1941 that he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying

Cross (DFC). This raid was delivered at low level against dock

buildings. Upon arriving at the target P/O Anderson circled the

area in Wellington R1588 until visibility allowed him to bomb

the target. His name was published in the London Gazette in July

1941 and his home newspapers carried the citation and his photo

that summer. At the beginning of July 1941 he transferred to the

Middle East and undertook the dangerous Ferry flight in a

Wellington from Portreath in Cornwall, to Gibralter, and thence

across the Mediterranean to Malta and then to Egypt. There he

joined 108 Squadron flying Wellington bombers and was awarded a

bar to the previous DFC when he brought home his crew in the

damaged Wellington T2832 on October 23rd, 1941. Sgt's C R Amos

and G R King appear to have been with him on that flight. With

damage preventing the landing gear from being lowered, four crew

members bailed out of the aircraft in friendly territory and P/O

Anderson had to bring the bomber in for a crash landing in the

desert. After recovering as best he could from his injuries,

after the crash, from Aug 1943 until June 1944, he flew

non-operationally with No.1 Radio School, mainly in Proctors.

From July to September 1944 he flew non-operationally with No.42

O.T.U No. 38 Group, mainly in Whitley bombers. Jim Anderson

corresponded with Steve Challen after the war and his son Jim

also provided copies of his flying log book and letters he wrote

from hospital. He was terribly burnt about his legs in the

crash, he recalled coming around after the crash and discovering

he was standing in flames. His injuries stayed with him for the

rest of his life, requiring dressing for many years. Despite

this and having a leg amputated in 1979, he took part in the

tragic Fastnet Race in the same year.

His log book records this fateful flight.

He wrote the following in a letter to his mother in August

1942: Well, there is nothing

much to tell about what happened. I was a passenger

and we left the day before to do it in one hop in one of our

new kites, we were to stay for a while and then take

others back. We had cloud for a long time and then

saw lights and knew we were O.K. Everybody in the back

relaxed and we lay down again. Dawn was breaking and

with a few streaks appearing in the clouds we thought

everything was lovely and all of a sudden we went

into some cloud and we saw the top of a hill go under

the escape hatch. Everybody grabbed for something and

in a split second we hit. I was lying on the bottom

of the machine bracing myself by the hands against a

piece of armour plating. When I came to the fuselage

was empty except for a pair of legs sticking out of the

tail. Apparently I must have bent in the

middle when we hit and banged my head on the armour

as I had quite a dent in my forehead together with a cut on

the chin and a piece off my left ear. At any rate

I was pretty badly concussed and have but very confused

memories of the happenings afterwards. The fog

lifted in the afternoon and we were found by the Ambulance

at about 3.30 in the afternoon.

According to what a couple of the others and myself

have pieced together the wing must have caught fire

later on. I can remember going toward it for some

reason or other and from the burns, I must have stood in

the burning wreckage. I can remember tying an old piece old

piece of dressing gown round my legs and then

wandering out when the Red Cross arrived. I was

still getting round quite well and when we got to Hospital I

thought I’d be able to get out in a tew days

after my legs had been dressed. After two days,

two of us were sent over to the workhouse at Daisy Hill

where I stayed for a fortnight. The other fellow only had

bruises and shock and went home after a week.

Cyril Rowland Amos was born in 1917 to Elsie and Harry

Amos, his father being a British merchant who lived in Argentina

between the wars.

Cyril remained in Hospital in Dundalk until the 19th of March

and was then sent across the border with Sgt Hayden. Having

survived the crash of AL577, Sgt Amos was posted as an

instructor to 22 Operational Training Unit between October and

December 1942.

He was commissioned as an officer in the RAF during the winter of 1942 and returned to flying duties. Cyril's luck ran out on December 31st 1943, only days after arriving with the training unit, when as pilot of Wellington X9666 from 21 Operational Training Unit he crashed into Ffrith Caenewydd, above Aberdovey, Merioneth in bad weather. Cyril died from his injuries shortly after this crash, which also killed two other airmen and injured two others. Cyril was buried in Tywyn Cemetery in Wales. His brother Harry was a wartime pilot also.

Lindsay Ross Williams was a New South Wales born pilot

from the Royal Australian Air Force. He was the son of Henry

Stanley and Elsie Ethel Mary Williams, of Five Dock, New South

Wales and born in 1915. Like many of the others, he had been

sent to Canada for training, being posted to the UK in 1941. He

served briefly with 11 OTU and 142 Squadron before transferring

to the Middle East in September 1941 after which he was posted

to 108 Squadron. He was 26 years of age at the time of his death

and before the war had been a farmer. Remembrance notices

in papers were posted by his mother and a fiance, Marriane

Warner.

Wilfred Bertrand Stephens, one of the pilot passengers on the aircraft came from Westminster, London. His Commonwealth War Graves Commission entry show that his remains were returned to Mill Hill Cemetery in the City. No next of kin is listed for him but the telegrams in Australian records indicate that his mother Mrs Stephens lived at 213 Watford Way, Hendon. His parents, Eleanor Larkman and Bertrand William Stephans married in 1921 and Wilfred was their only son as the inscription on his grave relates. His father was a veteran of home service with the Tank Corps in the First World War. It is not clear but his father had remarried in 1936 so Wilfred's mother may have passed away or separated from B W Stephens.

Thomas

Edward Pattison was a Durham born Wireless Operator/Air

Gunner flying as a passenger on AL577. At the time of the crash,

his parents lived in Highfield, Leicester. Tom Pattison

after his recovery had the unenviable task of contacting some of

his dead comrades families to let them know a little more about

their loved ones and their demise. Royal Air Force records show

that many of the families were written to and sent a stamped

addressed envelope to allow them contact Thomas. He wrote

to the Morey family in particular and in later life he was in

correspondence with Steve Challen in his research. An

extract of the letter to the Morey family can be found further

up the page. Tom married after the war but did not have

children. He passed away in Leicester in 1997. His sisters were

kind enough to contact in 2013 and pass on his photos.

Thomas

Edward Pattison was a Durham born Wireless Operator/Air

Gunner flying as a passenger on AL577. At the time of the crash,

his parents lived in Highfield, Leicester. Tom Pattison

after his recovery had the unenviable task of contacting some of

his dead comrades families to let them know a little more about

their loved ones and their demise. Royal Air Force records show

that many of the families were written to and sent a stamped

addressed envelope to allow them contact Thomas. He wrote

to the Morey family in particular and in later life he was in

correspondence with Steve Challen in his research. An

extract of the letter to the Morey family can be found further

up the page. Tom married after the war but did not have

children. He passed away in Leicester in 1997. His sisters were

kind enough to contact in 2013 and pass on his photos.

Sydney Frederick Hayden was another of the Australians on

board AL577 and like F/Lt Barrett, a member of the Royal Air

Force, rather than the Royal Australian Air Force. Sgt

Hayden had been born in 1920 in England and one year later

sailed with his mother Charlotte and older brother to Australia

where the family lived. His mother was Australian, as was

his bother Cecil, four years older than Sydney.

Sgt Hayden was badly injured in the crash, ending up

unconscious and with severe leg fractures. He was treated in

Newry and Stranmillis Hospital, Belfast for his injuries while

his father in Australia received messages advising him first

that his son was severely injured and interned in Eire. Further

telegrams over the following weeks would pass on the welcome

news that he was recovering and he was removed from 'dangerously

ill lists' on the 1st of May.

Such were his injuries, after further treatment, Sgt Hayden

returned to Australia in July 1943.

The address of his father, Sidney William Hayden, was given at

the General Electric Company in Sydney, Australia. Steve

Challen managed to make contact with Sydney Hayden in the 1980's

or 90's but it appears that he did not wish to discuss his

wartime experiences.

In the photo above, Sidney Hayden appears second from the right with three unknown comrades.

Sidney only died in 2005 and his grand daughter was so very kind to supply a great number of photo's of Sidney both before and after the crash. As discovered by Steve Challen, Sidney certainly never spoke much of his wartime experience with family either. They themselves were only too aware of his injuries that resulted in him walking with the aid of leg calipers even up to the 1960's and with crutches after that.

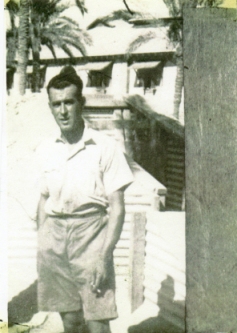

Andrew

Brownlie was a 29 year old aircraft fitter from Glasgow.

His great nephew was kind enough to provide the photos included

with this article. Among the photos was the one at left with him

in a distinctly tropical setting. Andrew was the only passenger

on the aircraft who was not aircrew, in that he would not have

flown combat missions while in North Africa. War Graves records

show that his trade was that of Fitter II (E). His sister was

100 years old in 2009. Their parents were Thomas and Marion

Brownlie.

Andrew

Brownlie was a 29 year old aircraft fitter from Glasgow.

His great nephew was kind enough to provide the photos included

with this article. Among the photos was the one at left with him

in a distinctly tropical setting. Andrew was the only passenger

on the aircraft who was not aircrew, in that he would not have

flown combat missions while in North Africa. War Graves records

show that his trade was that of Fitter II (E). His sister was

100 years old in 2009. Their parents were Thomas and Marion

Brownlie.

Walter P Brooks was just 20 years old and the son of Mabel and Walter Horace Harry Brooks. Walter was born in Wandsworth, London in 1921. His father passed away in 1944 in Leeds where he was living in 1942. Walter's brother was kind enough to send the photo of him.

George Buchanan was the son of Helen and William Buchanan and was from Paisley in Scotland. His parents lived at 14 Howe St in the town. Like many of the dead from AL577 he was returned to his parents for burial. F/Sgt Buchanan was another of the pilots destined for the UK and the collection of new Liberators.

Carlton S Goodenough was a 28 year old navigator passenger on the aircraft. The son of Wright E. and Eva Stokes Goodenough from Bury, Quebec. Carlton was a teacher of seven years experience. He married his wife, Margaret Bagley in 1937 and a son, Thomas was born the following year. Carlton enlisted in July 1940, and had arrived in the UK in April 1941. F/Sgt Goodenough was interred in Belfast City Cemetery. His photo on this page was found on the McGill University memorial website on his individual page. His son Thomas passed away in 2005.

Leslie George Jordan was 20 years old and the son of

John B. Jordan and Rose Jordan, of Portslade. He is found

residing with his parents at 235 Old Shoreham Road in Portslade

on the 1939 register. On that, he is listed as being a

scholar but also being a member of 226 Battery, of the Royal

Artillery. Leslies's father was a veteran of the First

World War

George Frederick King,

one of two Canadians on the aircraft came from Ontario. The 25

year old King, the son of Philip and Belinda King, had engaged

in some flying before enlistment in April 1940, leaving his job

in New Toronto with the Campbell Soup Co. He arrived in the

United Kingdom in November 1940 after training in Canada. His

first service posting was with 103 Squadron from March 1941 as

an Observer, or navigator. He was later again posted to the

Middle East and his service file indicates he joined 108

Squadron in August 1941. K F Vare the officer who had to take

over 108 Squadron from the deceased W/Cdr Wells wrote to

George's mother after his death: "Your

son had been with the Squadron since 6th August, 1942, and

had made twenty-nine raids against the enemy. His Flight

Commander has always spoken well of his work. His zeal for

operations were remarkable and we all, here, feel it very

strongly that he has gone." Sgt King was buried

on 21st March at Belfast City Cemetery, alongside his comrades.

George Frederick King,

one of two Canadians on the aircraft came from Ontario. The 25

year old King, the son of Philip and Belinda King, had engaged

in some flying before enlistment in April 1940, leaving his job

in New Toronto with the Campbell Soup Co. He arrived in the

United Kingdom in November 1940 after training in Canada. His

first service posting was with 103 Squadron from March 1941 as

an Observer, or navigator. He was later again posted to the

Middle East and his service file indicates he joined 108

Squadron in August 1941. K F Vare the officer who had to take

over 108 Squadron from the deceased W/Cdr Wells wrote to

George's mother after his death: "Your

son had been with the Squadron since 6th August, 1942, and

had made twenty-nine raids against the enemy. His Flight

Commander has always spoken well of his work. His zeal for

operations were remarkable and we all, here, feel it very

strongly that he has gone." Sgt King was buried

on 21st March at Belfast City Cemetery, alongside his comrades.

The photo at left was provided by his niece and shows George

standing at the right with a colleague named George Kusiar.

The Toronto Star on the 19th of March 1942 reported on his

death having been notified to his parents:

New Toronto, March 19-Flight-Sergeant

George F. King, son of Mr. and Mrs. Philip King 5th St., New

Toronto, lost his life in action near Dundalk, Eire, on

March 16, according to a cable received by his parents this

morning.

"I don't quite understand it." said Mr. King.

"George sent us a cable from another front just last week. I

don't see how he could get into action in Ireland so

soon."

Flight-Sergeant King joined the R.C.A.F. shortly after the

declaration of war and had been overseas more than two

years. He was one of the first observers to graduate from

Malton air school.

He was born in Toronto 24 years ago. He was a graduate

of Mimico high school where he established a fine athletic

record. He is survived by his mother and father and two

sisters, Mrs. Lorne Sones of Mimico and Greta Muriel King,

who lives at home.

Herbert W T Sloman came from New South Wales, the only son

of Mary Alice and George Sloman. He enlisted in September 1940

and embarked for Canada in January 1941 where he trained as a

pilot with 7 Service Flying Training School at Fort MacLeod,

Alberta. While there, near the end of his training, he was

lucky to survive a night time landing in Avro Anson, serial

number 1817. The aircraft swung on landing, ground looped

and was badly damaged. Herbert was somehow not injured and

received a reprimand for his landing. He graduated in

Course 22 on the 5th of May 1941. From there he shipped

out to the United Kingdom arriving in June 1941. After further

crew training in the UK at 20 OTU, he was posted to 40 Squadron

at Harwell. He was posted to the Middle East in October

1941, joining 108 Squadron in November. He was buried on March

21st in Belfast. Herbert had three sisters surviving him.

On the same day as the crash of Liberator AL577, only a few

miles north in Northern Ireland, another RAF aircraft, this time

Vickers Wellington X3599 from 57 Squadron crashed in the hills

above Newcastle, killing five men. Two members of this

crew, along with five of the crew of AL577, Barrett, Goodenough,

King, Sloman and Williams were buried on the 21 March 1942 in

Belfast City cemetery. Canadian newspapers reported on

this in particular due to there being three RCAF members between

the two aircraft.

The crash site, shown in the 1942 photo at the start of this

article, has been marked by memorials at the site since

1993.

This panorama photo of the site from the lower slopes of

Slievenaglogh shows Annaloughan Mountain in the right background

and some high points to the right.

The incident was raised in the United Kingdom Parliament by

Ralph Glyn, the representative for XXXX. In this he asked

Sir Ralph Glyn, - To ask the Secretary

of State for Air, whether an enquiry was held into the crash

of a Liberator aircraft on the 16th March last at

Jenkinstown, Dundalk, Eire, whilst on passage to this

country from the Middle East; how many lives wore lost and

how many persons injured; whether he is aware that the

relatives of the dead have been unable to recover the

personal effects carried by the deceased officers and men;

what became of other material being conveyed in the

aircraft; and what was the cause of the accident.

In 1993, local people from

Louth including Noel Roddy raised the memorial plaque near the

spot. The site is a short walk off a road and not easy to access

due to the condition of ground etc. From the heights above the

crash site one can on a very clear day see down the the east

coast and see the peak of the Sugar Loaf Hill in Wicklow, south

of Dublin city. The memorial plaque for AL577 with the crash

location in the background, in the dip below the lumps on the

hill.

In 1993, local people from

Louth including Noel Roddy raised the memorial plaque near the

spot. The site is a short walk off a road and not easy to access

due to the condition of ground etc. From the heights above the

crash site one can on a very clear day see down the the east

coast and see the peak of the Sugar Loaf Hill in Wicklow, south

of Dublin city. The memorial plaque for AL577 with the crash

location in the background, in the dip below the lumps on the

hill.

A new memorial was raised at the

site in the 2000's and funnily enough, used the names list from

this site. This memorial plate later had a die cast metal

model of a Liberator in Coastal Command colours. This

memorial was located close to the location of a sizeable patch

of ground that even in May 2022 was largely devoid of

vegetation. Close inspection of that patch of ground

reveals hundreds of tiny green/blue strands of corroded copper

wire, both single strand and braided types. Various items

of broken glass or perspex can also be seen glinting in the sun

and screws and washers can still be found. Adjacent to

that patch of ground is a rock on which locals had painted a

cross in the earliest form of memorial.

A new memorial was raised at the

site in the 2000's and funnily enough, used the names list from

this site. This memorial plate later had a die cast metal

model of a Liberator in Coastal Command colours. This

memorial was located close to the location of a sizeable patch

of ground that even in May 2022 was largely devoid of

vegetation. Close inspection of that patch of ground

reveals hundreds of tiny green/blue strands of corroded copper

wire, both single strand and braided types. Various items

of broken glass or perspex can also be seen glinting in the sun

and screws and washers can still be found. Adjacent to

that patch of ground is a rock on which locals had painted a

cross in the earliest form of memorial.

In March of 2022, to mark the 80th anniversary of the crash,

Noel Roddy's son, Derek, with the aid of friends including

Ciaran Gormley and Archie Murphy, raised a new memorial on the

site using a number of parts from the aircraft, as well as a die

cast model of a Liberator. The memorial was overflown on

the 16 March 2022 by the Irish Coast Guard helicopter based at

Dublin airport, call sign Rescue 116.

The memorial sits roughly on the spot where the wreckage of the

tailplane can be seen in the wartime photos. The photos

below were provided by Derek. The memorial has been

orientated such that the table and aircraft are pointing roughly

along the final tragic path of Liberator AL577. Noel Roddy

understood that one engine was found

A patch of ground near the rocky outcrop is to this day almost

devoid of vegetation. It is shown beow with the main 2022

memorial in the background.

Even a cursory search of this patch will reveal many many

strands of corroded electrical wiring, screws and mall pieces of

aircraft structure. The photo of some of the finds reveals

small screws, pieces of glass or perspex.

The mountains in this area would claim the destruction of two more aircraft during the war. An RAF Hudson crashed in September 1941 killing 3 men while a P-51 Mustang fighter of the US Army Air Forces crashed in September 1944 killing its pilot.

Compiled from various sources by Dennis Burke, Dublin, 2019: Including the Morey, Tolson, Anderson, Pattison, Brownlie and Brooks families. The service records of all Australian and Canadian aircrew members; the Irish Army Archive files in Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin; the CWGC. And my friend, Heno, for the use of his photos.

W/Cmdr (Pilot) Richard John WELLS DFC

39918 +

W/Cmdr (Pilot) Richard John WELLS DFC

39918 + P/O

(Pilot) John Peile TOLSON 67640 +

P/O

(Pilot) John Peile TOLSON 67640 +  Sgt

(Obs/Nav) Paul Herrick MOREY 917067 +

Sgt

(Obs/Nav) Paul Herrick MOREY 917067 +  Sgt

(WOP/Air Gnr) Henry James GIBBONS 948393 +

Sgt

(WOP/Air Gnr) Henry James GIBBONS 948393 +