Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress, 42-97747, Mid Atlantic, May 1944

The 16th of May 1944 seen one of the stranger incidents included in the list of foreign aircraft crashes in or around Ireland. In reality it didn't happen 'near' Ireland and the crew members never set foot on Irish soil but they were plucked from the wide Atlantic by an Irish ship!

The pilot of Boeing B-17G serial number 42-97747, the wonderfully named Clarence W Fightmaster, was in command of the aircraft on a transatlantic ferry mission, delivering the new bomber to the Eighth Air Force in England for the ongoing bomber offensive against Germany. The crash report in the US Air Force archives includes his report filed in the aftermath of the incident and tells the story in simple terms:

"Last radio contact with any station

was made with Goose Bay at the time flight altitude of

11,000 ft. was reached. We proceeded on course as briefed to

the navigator.

No other radio contact was made. Our liaison

transmitter was not working properly, apparently due to a

broken trailing wire antenna. Many attempts were made for

[text unreadable] and other radio aids.

We flew out our ETA plus forty min., and at no time

could we pick up the Meeks radio, or any other radio. The

navigator made several shots, but they showed to be roughly

several hundred miles off DR course, so we followed

Navigators briefing and remained on DR.

Due to the overcast and following flight plan the

Navigator assumed a DR position and altered course for

Stornaway. No indication was ever found of destination so at

the end of new ETA plus thirty min. course was altered to

the east in approximate direction of land. A London civilian

radio station was also [text unreadable] up

on the compass that roughly indicated that direction.

With about thirty min. of fuel remaining and no

indication of land a ditching was made beside a tramp

steamer approximately 160 miles south west of the Irish

coast. Dingy procedure was followed and all of the crew were

rescued. The ship remained afloat for thirty min."

In the above account, the following terms are:

ETA - Estimated Time of Arrival

DR - Dead reckoning

The Army Air Forces report includes the following summary of

the event:

"On May 16 1944 at approximately 1200

GMT, B-17G 42-97747 ditched at 49" 46'N 13" 01'W.

This ship was cleared from Goose Bay,

Lab. destined from Meeks Field, Iceland, Pilot Fightmaster,

Clarence, 2nd Lt , AC, O-1291613.

According to the pilot and crew no

radio contact was made from the time they took off or left

Goose Bay the navigator was depending entirely on DR, and

not celestial. He took several shots which put him

several hundred miles south of course, but according to the

navigator remained on DR, according to briefing.

The ship finally ditched appr. 1000

mi. S.E. of destination due to lack of fuel. The ship

was ditched beside a tramp steamer which picked up the crew.

Recommend that Briefing Officers

stress a point that celestial navigation should be depended

on when shots are taken rather than DR. In addition it

is also recommended that navigators before making an

overseas flight should have navigation equipment

checked. This particular navigator did not have his

sextant checked in the last six months."

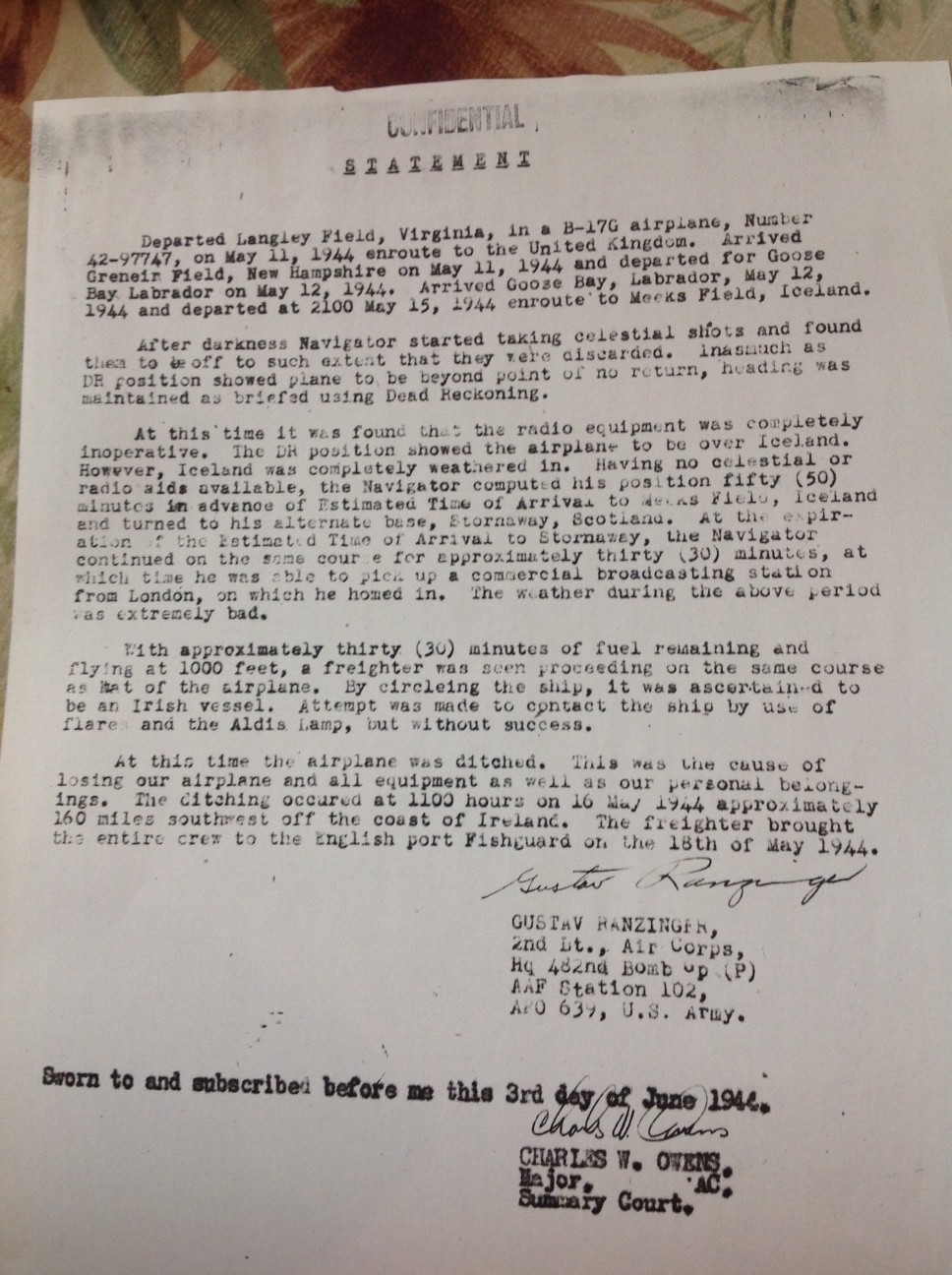

Gustav Ranzinger the navigator had his own report on the

ditching in the files he left his family.

The ship they landed beside was the Irish registered SS

Lanahrone under the Command of Captain Timothy Hanrahan. Frank

Forde, in his book, The Long Watch, explains that she was on a

its return voyage from Saa Tome off modern day Gabon, West

Africa. Evidence provided by Gustav Ranzinger shows that the

vessel called to Fishguard in the UK to disembark its unexpected

passengers. Forde mentions only that the Lanahrone

returned to Dublin early in June 1944, with no mention made of

its rescue adventure. The vessels movement card in the UK

national archives also confirms this, with the arrival at

Fishguard being on the 18 May 1991.

The Lanahrone had been built in Scotland in 1928 for the

Limerick Steamship Company. She plied her trade between

Ireland and the UK throughout the 1930's, her name appearing in

the shipping news in newspapers at all times. R J Scott in

a 1982 "Ships Monthly" article mentions that in October 1936,

the Lanahrone was present to rescue two German aviators who had

crashed off the Weser. It was the first of a number of

rescues the Lanahrone found itself involved in. The

Lanahrone's first brushes with war were in the late 1930's while

sailing to Spain for cargo's during that nations civil war.

The start of the war would see neutral Ireland almost bereft of

shipping and the vessels that were available were used where

ever they were needed, including voyages beyond what the vessels

would have been expected to do in peace time. On the 27

August 1940, the Lanahrone picked up 18 survivors of the British

ship Goathland, which had been sunk two days previously by a

German aircraft. A year later and while sailing with the

British convoy OG71 to Gibraltar, her sister ship Clonlara was

sunk and the surviving ships had to make for Lisbon to escape

the German onslaught. R J Scotts article mentions that

Lanahrone in early 1944 made a transatlantic voyage to Saint

John, New Brunswick to load wheat, having sailed a number of

times to West Africa earlier in the year. October 1945

would see her providing assistance to the sinking Royal Navy

submarine HMS Universal. Then finally, in August 1949, the

Lanahrone again was on hand after the ditching in Galway Bay of

Transocean Airlines

Douglas Skymaster N79998. On this occasion however, she

was only able to recover bodies of some of those who died.

She seems to have sailed thereafter without incident and was

broken up in Holland in 1959.

An intriguing notice found in the Wicklow People of 30 November

1946, in describing the contents of the latest Maritime and

Aviation Magazine includes the following:

A wartime incident which occured to the

Limerick Steamship company's "Lanahrone" is the basis for

Malachy Hynes' story, "The Lanahrone Comes Through".

Mr Hynes contrives to get a deal of atmosphere and shrewd

characterization in this story of an Irish Skipper and crew

who pick up, under difficult circumstances, an American

flight crew.

And sure enough, that edition of the magazine carried a two

page story written by Malachy Hynes and based on a 'talk' with

Captain Hanrahan about the rescue.

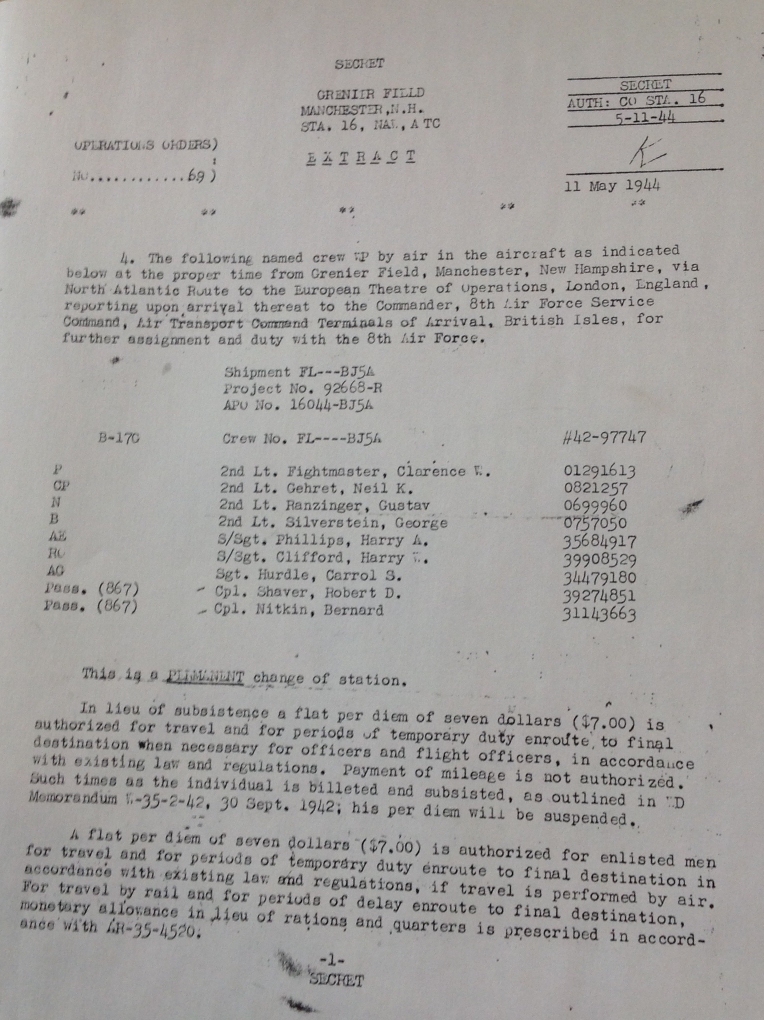

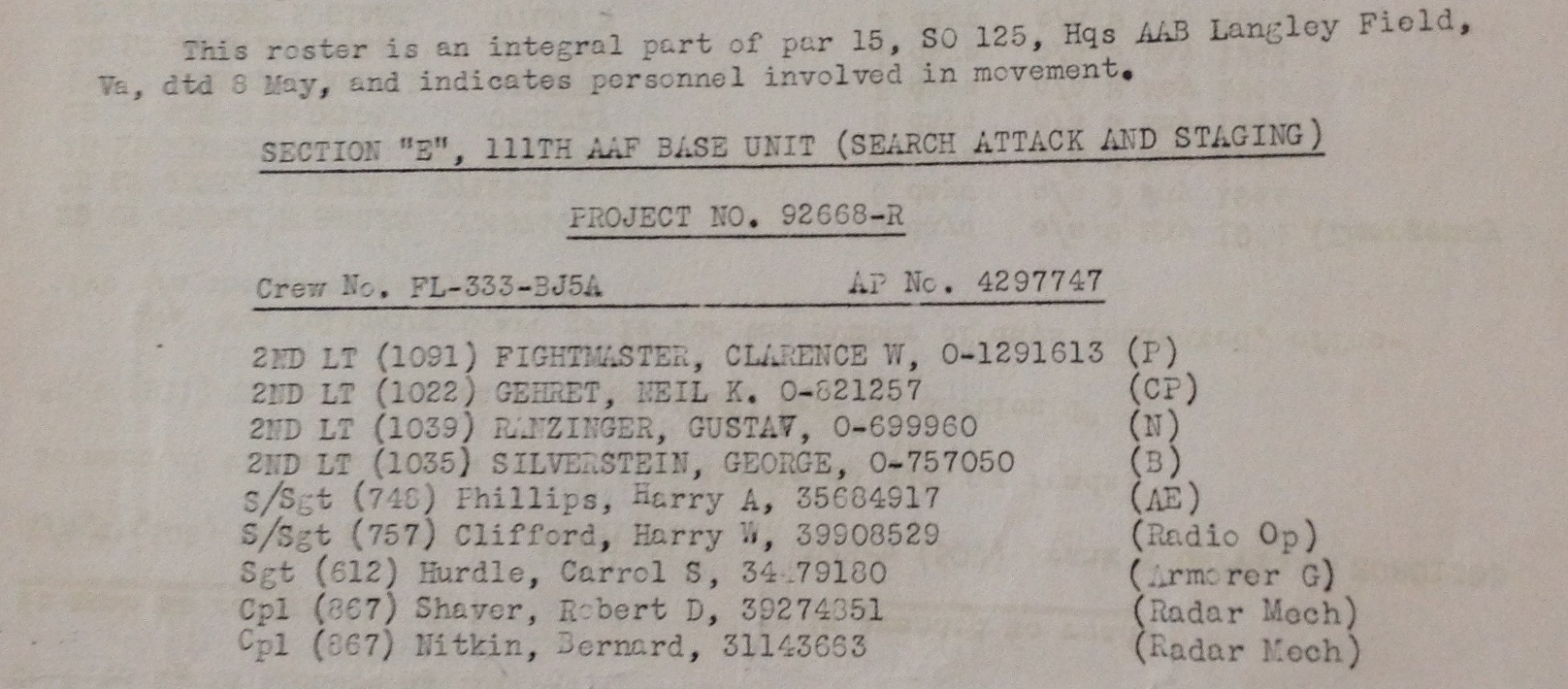

The crew of 2/Lt Fightmaster's aircraft consisted of seven aircrew and two radar technicians.

2/Lt Clarence W Fightmaster O-1291613 (Pilot)

2/Lt Neil K Gehret O-821257 (Co-Pilot)

2/Lt Gustav Ranzinger O-699960 (Navigator)

2/Lt George Silverstein O-757050 (Bombardier)

S/Sgt Harry W Clifford 39908529 (Radio Operator)

S/Sgt Harry A Phillips 35684917 (Engineer)

Sgt Carrol S Hurdle 34479180 (Air Gunner)

Cpl Bernard Nitkin 31143663 (Passenger, Radar Technician)

Cpl Robert D Shaver 39274851 (Passenger, Radar Technican)

After their rescue from the sea, three of the officers and all

the sergeants were posted to the 91st Bomb Group flying from

Bassingbourne in . The 91st Bomb Group website records their

arrival as follows, with EM indicating Enlisted Men:

11 June 1944 – The following EM and Officers assigned and joined

from AAF Station 112: 2nd Lt. Clarence W. Fightmaster, 2nd Lt.

Neil N. Gehret, 2nd Lt. George Silverstein and S/Sgt. Harry W.

Clifford. The following EM assigned from AAF Station 112, DS to

AAF Station 172: S/Sgt. Harry A. Phillips, Sgt. Carrol S.

Hurdle, Sgt. Charles R. Knox, Sgt. Robert C. (Last name

illegible.) Sgt. Virgil S. Skagsbergh

Just two days later and they would be off on their first bombing mission to Hamburg, 2/Lt Gehret getting to sit this one out while 2/Lt Fightmaster flew as co-pilot to 2nd Lt. Neiswender. The mission reports can be read on the www.91stbombgroup.com website. Five days later and Wally Fightmaster would lead his crew back to Hamburg. After one more mission to Berlin, 2/Lt Fightmaster no longer appears in the mission records of the 401st Bomb Squadron, but Gehret, Silverstein, Phillips, Hurdle and Clifford continue to fly missions into Autumn and winter of 1944 with other pilots and thereafter the newly promoted 1/Lt Gehret takes command of his own crew. Crew lists are varied at this point and different crews flew on different days. The enlisted men may have been transferred to another Squadron in the 91st in July 1944 after completing about 17 missions.

Clarence W Fightmaster was an Oklahoma born

pilot, the son of Irene and Eddie Fightmaster. Born in

1919, he had enlisted in 1940 and married in Florida in December

1943. He was an industrial engineer and an expert at industrial

equipment like boilers and pumps. The Daily Oklahoman

newspaper reported in Jun 1943 that he was being posted to

Courtland Field, Alabama for cadet pilot training. In

newspapers, he was recorded by his middle name Wallace

Fightmaster. His family recalled that Clarence suffered

lacerations to his head during the ditching.

Clarence W Fightmaster was an Oklahoma born

pilot, the son of Irene and Eddie Fightmaster. Born in

1919, he had enlisted in 1940 and married in Florida in December

1943. He was an industrial engineer and an expert at industrial

equipment like boilers and pumps. The Daily Oklahoman

newspaper reported in Jun 1943 that he was being posted to

Courtland Field, Alabama for cadet pilot training. In

newspapers, he was recorded by his middle name Wallace

Fightmaster. His family recalled that Clarence suffered

lacerations to his head during the ditching.

In a letter, his wife Lois recounted what she knew of the

landing, as told to her by Neil Gehret and George

Silverstein: "The B-17 Wally was

piloting was one of a group that had to be ferried overseas

by their crews because they were fitted with (secret) radar

that enabled them to fly at 30,000 feet—quite high in those

days. When their fuel began to run low, they

jettisoned everything—all the clothes they weren't wearing,

all their belongings---everything. They were carrying two

passengers who were not crew members. When those in

the plane spotted the ship, they realized that ditching was

their best chance to survive. As the plane splashed

down on the water, Wally went through the windscreen,

injuring his head and cutting up his hands. One of the

passengers had hysterics and had to be pulled bodily from

the craft. Gus Ranzinger, the navigator, apparently

sustained an injury that destroyed his balance. The

seas, reportedly, were 20 feet. I do not know how the

ship's crew got the plane's crew aboard, but one thing Wally

did relate was that he got his first taste of Irish whiskey

shortly thereafter. The ship had a cargo for London,

so, the survivors were informed, they could go to London and

rejoin the war effort or they could go back to Ireland and

be interned for the duration, Being patriotic,

foolish, young men, they opted for London, where they

were treated like spies because of their "irregular"

entry. Wally spent 6 weeks in hospital, Gus, longer.

When Wally finally went back on duty,he got opportunities to

go to Ireland on leave, where he bought me beautiful tweed,

and where he remembered fondly having steak with an egg on

top.

Clarence suffered

head injuries in the ditching and later was transferred to

aircraft ferrying activities according to his family.

Wally, as he was

known to family and friends, passed away in Oklahoma in

October 1980. His wife and son kindly provided the photo on

this page.

Neil K Gehret was a Pennsylvanian born

pilot. He enlisted in July 1942 in Allentown. Following his

arrival in the UK he was posted to the 91st Bomb Group but had

returned to the United States by December 26th 1944. Neil was

featured in his local Florida community newsletter in July 2014,

with a group of similar veterans reflecting on being fathers. The

article can be read here. It records for Neil, Neil

Gehret served in WWII in the Army Air Force, as a pilot on a

B-17. After the war he went back to a job as a controller for

various manufacturing companies in south Florida.

Neil K Gehret was a Pennsylvanian born

pilot. He enlisted in July 1942 in Allentown. Following his

arrival in the UK he was posted to the 91st Bomb Group but had

returned to the United States by December 26th 1944. Neil was

featured in his local Florida community newsletter in July 2014,

with a group of similar veterans reflecting on being fathers. The

article can be read here. It records for Neil, Neil

Gehret served in WWII in the Army Air Force, as a pilot on a

B-17. After the war he went back to a job as a controller for

various manufacturing companies in south Florida.

In 2008 Neil was able to pass on the following narrative via his care assistant: After completing radar bombing training for the bombadier at Langley Field, Virginia, we left England by B-17 by the northern route. Our first stop outside the U.S. was at Goose Bay, Labrador. Our departure from Goose Bay was delayed because it had snowed during the night. Our next stop was to be Iceland. As we flew towards Iceland we found all the radio equipment onboard was not operating. Without radio contact, it was not possible to land in Iceland. At our briefing before leaving Goose Bay, we were told if it was not possible to land in Iceland, our alternative landing field was Stournway, Scotland. Also, we learned that our navigator's sextant was missing, making celestial navigation impossible. Following a compass course without knowledge of wind speed or direction would cause drift from the compass course. After many hours in the air and fuel running low, we spotted a ship. As we circled the ship, the radio operator flashed in morse code to the ship requesting directions to land. The ship responded with the code letter of the day identifying them as a neutral. It became necessary to ditch the plane while we still had fuel to make a power-on landing in the water. We ditched near the ship, inflated the life rafts, and eventually we were picked up. We were told by the crew of the Irish ship that they got the coal to run the ship from England, and had to report to an English port for inspection of their cargo before they could dock in Ireland. Upon arrival in the English port we were sent for more combat flight training before our arrival at our bomb group to engage in bombing missions for which we were trained.

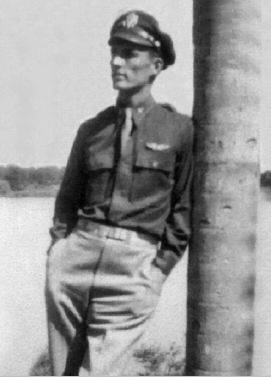

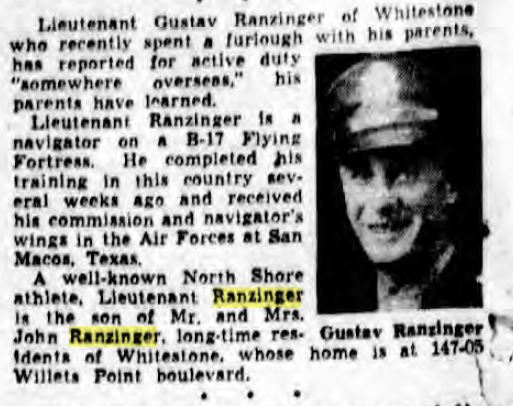

Gustav

Ranzinger was a German born immigrant born in 1918. In

1923 he arrived in New York with his mother and sister,

traveling to meet his father John who had preceded them. Growing

up in New York city, the 1940 census shows Gustav to be working

as a Bank Clerk. He was often reported upon prewar

for his local newspaper due to his involvement with local tennis

competitions. He enlisted in the Air Corps in 1942. The

small article at right was published by the XXX in XXX and goes

on to say: Lieutenant Gustav

Ranzinger of Whitestone who recently spent a furlough with

his parents has reported for active duty "somewhere

overseas" his parents have learned. Lieutenant Gustav

Ranzinger is a navigator on a B-17 Flying Fortress. He

completed his training in this country several weeks ago and

received his commission and navigator's wings in the Air

Forces at San Marcos, Texas. A well-known North Shore

athlete, Lieutenant Ranzinger is the son of Mr and Mrs John

Ranzinger, long term residents of Whitestone, whose home is

at 147-05 Willets Point boulevard." Beyond

his presence on B-17 42-97747, little more is known of Gustav's

service career as he does not appear to show up the the records

of the 91st Bomb Group. His family understand that his hearing

was damaged during the landing in the sea and this resulted in

him being removed from flying duties. His service records

indicate to them that he served with the 94th Bomb Group.

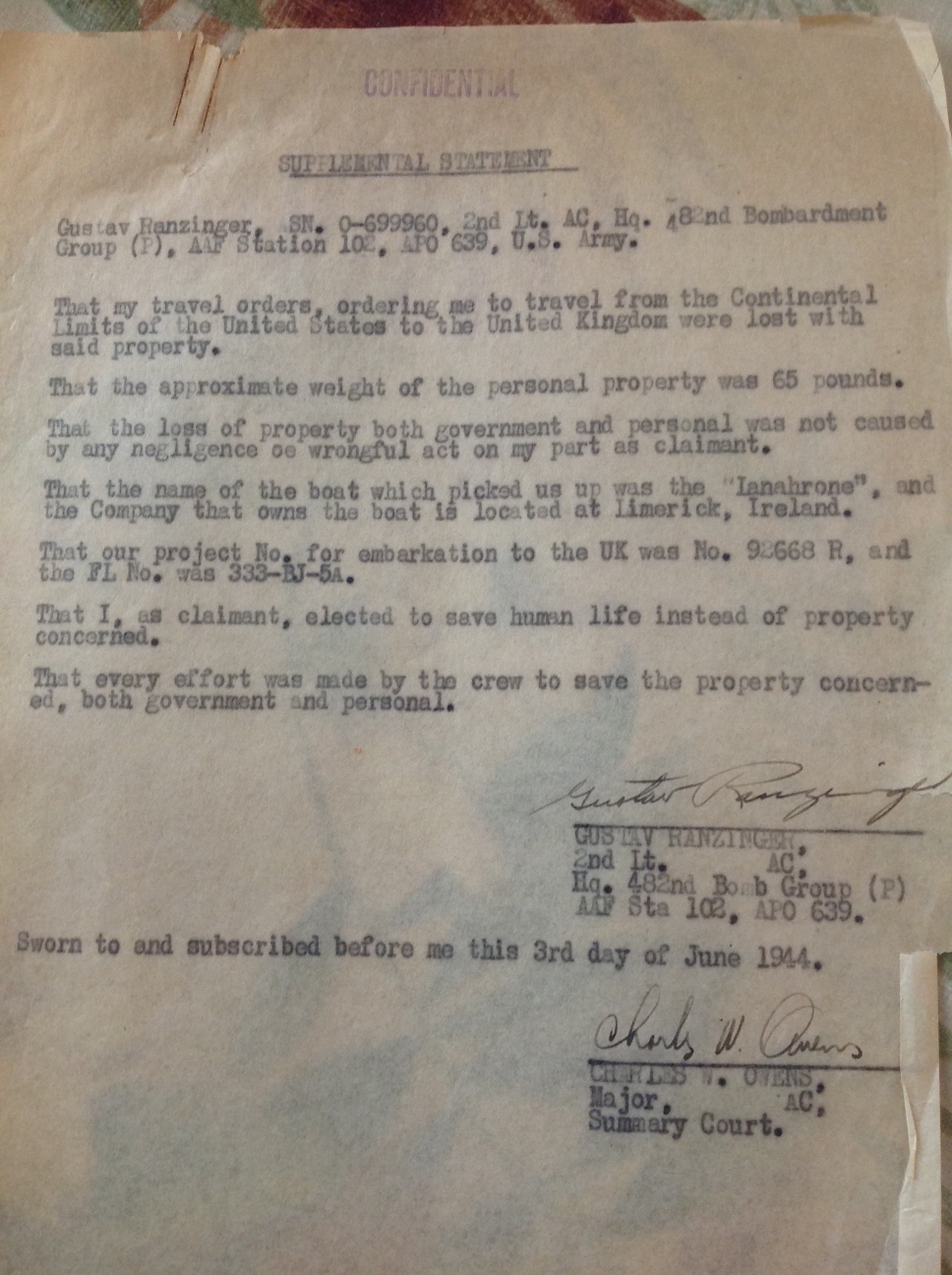

Documents kept by Gustav show him as being posted to the 482nd

Bomb Group (P) in June 1944.

Gustav

Ranzinger was a German born immigrant born in 1918. In

1923 he arrived in New York with his mother and sister,

traveling to meet his father John who had preceded them. Growing

up in New York city, the 1940 census shows Gustav to be working

as a Bank Clerk. He was often reported upon prewar

for his local newspaper due to his involvement with local tennis

competitions. He enlisted in the Air Corps in 1942. The

small article at right was published by the XXX in XXX and goes

on to say: Lieutenant Gustav

Ranzinger of Whitestone who recently spent a furlough with

his parents has reported for active duty "somewhere

overseas" his parents have learned. Lieutenant Gustav

Ranzinger is a navigator on a B-17 Flying Fortress. He

completed his training in this country several weeks ago and

received his commission and navigator's wings in the Air

Forces at San Marcos, Texas. A well-known North Shore

athlete, Lieutenant Ranzinger is the son of Mr and Mrs John

Ranzinger, long term residents of Whitestone, whose home is

at 147-05 Willets Point boulevard." Beyond

his presence on B-17 42-97747, little more is known of Gustav's

service career as he does not appear to show up the the records

of the 91st Bomb Group. His family understand that his hearing

was damaged during the landing in the sea and this resulted in

him being removed from flying duties. His service records

indicate to them that he served with the 94th Bomb Group.

Documents kept by Gustav show him as being posted to the 482nd

Bomb Group (P) in June 1944.

He was able to retain copies of the original movement orders

that the crew of 42-97747 received during their departure for

Europe.

A further movement order supplement repeated the information

above but with all MOS.

In these documents Gustav is making a loss claim report for his lost equipment and belongings. The documentation retained by Gustav includes his claim form for his belongings and equipment that were lost with the ditching of 41-97747. This document is one of the only contemporary documents that mentions the name of the ship.

His rescue at sea earned him the ability to request a Goldfish

club membership, a club for those who had been saved by

emergency flotation equipment fitted to aircraft.

His daughter wrote of her father: "My

Dad never spoke of it. He was angry that they removed

him from flying due to his injury from the ditching.

He fought for years to prove...he finally did...that his

hearing loss was service connected. It was Meniers

syndrome from the shock of the crash. They tried to

say it was nerves when it happened. The only stories I

remember hearing was when he was in the hospital. He

spoke of hearing the bombers struggling to take off and some

not making it with the heavy bomb load. Also, one of

his last assignments was stateside discharging GIs.

Apparently he signed Ronald Reagans discharge papers...so we

were told...not proven.

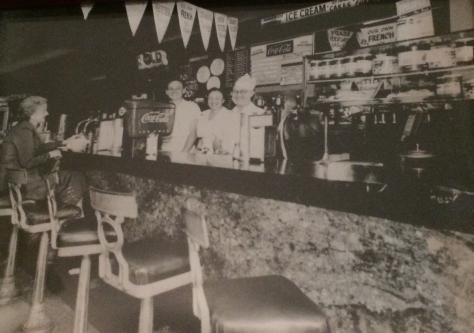

After the war my Dad went into business with

his father and started Broadway Confectionery..an ice cream

parlor in Flushing Queens. I included a picture..from

left to right my Dad, his sis and Father. It was better

known as the Slab...from the marble slab counters.

That picture hangs on the wall still today. It is a

coffee shop and we recently went there when we visited my

Dad and family in Flushing Cemetery. He had the store

until about 1959.

After the war my Dad went into business with

his father and started Broadway Confectionery..an ice cream

parlor in Flushing Queens. I included a picture..from

left to right my Dad, his sis and Father. It was better

known as the Slab...from the marble slab counters.

That picture hangs on the wall still today. It is a

coffee shop and we recently went there when we visited my

Dad and family in Flushing Cemetery. He had the store

until about 1959.

He bounced around a few years before becoming an

insurance agent with Prudential. He retired in the late

eighties after many years with them. He then battled

prostate cancer and passed away April 4, 1990. He and my Mom

married in 1946."

He passed away in New York in March 1990.

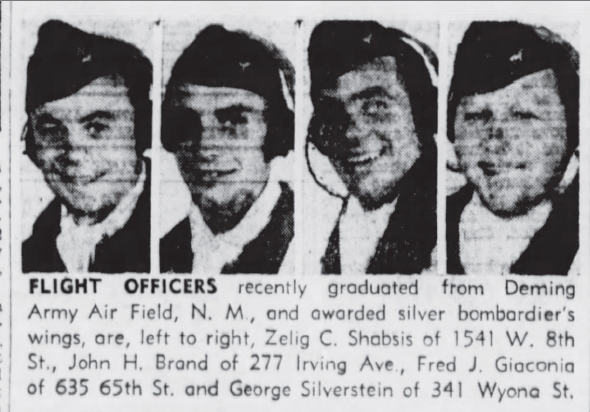

George

Silverstein was a resident of Brooklyn, New York, born in

1915, the son of Sam and Fannie Silverstein. He along with two

other brothers Milton and Martin, served during the war. George

was awarded the Air Medal and the Distinguished Flying Cross

(DFC) during his service. He flew as bombardier under the

command of a number of pilots up to at least the end of November

1944 with the 401st Squadron.

George

Silverstein was a resident of Brooklyn, New York, born in

1915, the son of Sam and Fannie Silverstein. He along with two

other brothers Milton and Martin, served during the war. George

was awarded the Air Medal and the Distinguished Flying Cross

(DFC) during his service. He flew as bombardier under the

command of a number of pilots up to at least the end of November

1944 with the 401st Squadron.

George is shown on the right of the photo at left, with his

brother Milton on the left. Milton served in the Signal

Corps during the war.

He passed away in 1985 in the Bronx, New York.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 22 Oct 1943 carried a photo of

George on the occasion of his graduation as a bombardier.

Harry W Clifford was born in 1923 in Grand Junction,

Colorado to Harry and Eva Clifford, moving later with his family

to live in Weber County, Utah. His high school education

was in Westminster College in Salt Lake City. He enlisted

at the start of February 1943 and served through until release

from the services in November 1945. The Salt Lake Tribune

of Sep 5, 1943 records him as having graduated from radio school

at Scott Field, Illinois. At that time his father and step

mother, Harry and Channie Clifford lived at 704 1/2 West 2nd

Street in the city. Harry's brother Raymond L Clifford also

served in England with the Army Air Forces, but the exact

details have yet to be determined. He was awarded the DFC

as well as the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters during his

time with the 91st Bomb Group.

After the war he became a special education teacher in

Wilmington, Delaware and his obituaries recorded his having

devoted many hours and money fighting for the rights of children

with Special Needs.

His great love however was dancing. He was a ballroom

dancer and ran a dance studio in New York and later the

Wilmington and Newark areas. He was said to have learned

to dance while serving in England. He was often mentioned

and interviewed in Delaware newspapers about dancing. And

he was often recorded in those interviews as having served in

the 401st Squadron, 91st Bomb Group as a radioman. The

Morning News, from Wilmington, Delaware ran a long article about

Harry and his dancing career on the 3rd of February 1983.

The article included: His love

affair with dance began while he served as a radio operator

with the Eighth Air Force in England during World War II.

While checking out the night life in London, he had a rude

awakening. "None of the American GIs knew how to dance or

knew only how to jitterbug. The English girls and other

Europeans were fantastic dancers. We didn't how to dance

with the girls we met." Clifford began taking dance lessons

from English instructors.

Soon he was teaching other GIs.

He never married and had no children. Harry passed away

in December 1987 in Salt Lake City from cancer, and was survived

by his step mother and four sisters.

Harry A Phillips was born in 1923 in Campbell,

Kentucky. Harry passed away in September 1984 and had told his

family little about his wartime service. They did know that he

carried out 31 missions with the 91st Bomb Group and he had told

family members that he had been shot down over the Irish sea and

had to be rescued. As the family understood it, he was given a

long recovery period in Colorado after this, however the facts

are unclear. Harry was the airplane mechanic - gunner

within the crew, evidenced by his Military Occupation Specialty

(MOS) of 748.

Harry passed away in Kentucky in September 1984 and is buried

there in Campbell County.

His family had the following two photos of Harry with wartime

comrades, and it appears it shows the enlisted men group that

stayed together throughout 1944.

The names here , listed from left top are: "Harry,

Lee, Clifford, Hurdle and Sandy" Comparing the faces from

photos it is assumed that the men are as follows:

Harry is Harry A Phillips;

Lee: its not clear who this might have been based on the names

presented in the 401st Bomb Group diaries.

Clifford: Harry W Clifford;

Hurdle: Carroll S Hurdle

Sandy: It is expected that this was Robert C Sandblom who served

with Hurdle, Clifford and Phillips during combat based in

the UK.

They together served with a numbers of pilots including

2Lt. Charles K. Neiswender O-803255, Clarence Fightmaster, and

Jack Oates.

This additional photo shows, it seems, the same five

individuals, albeit this time without names recorded. They

appear to be:

Rear row, left to right: Harry W Clifford, Harry A

Phillips, Carroll S Hurdle

Front row, left to right: Possibly Robert C Sandbolm and perhaps

the in the individual named 'Lee" in the other photo.

Carrol S

Hurdle came from Marshall County, Missisippi. He studied

at Mississippi State University and was working before the war

in a sales roles. He died in November 1983 in his native

Marshall County. The American

Air Museum website also has a page dedicated to Sgt.

Hurdle however it too mentions that he spoke little about his

wartime experiences. Carroll Simpson (“Simpson”) Hurdle, oldest

child of Donny Oscar Hurdle and Cornelia Bell (Bull) Hurdle, was

born 7 October 1908 (Mississippi) and died 17 November 1983,

married Margaret Louise (“Louise”) Winter who was born 19 April

1915 (Holcomb, MS) and died 23 February 2008. Simpson and Louise

are buried in Slayden Cemetery (Marshall County, MS). They had

no children but are fondly remembered by relatives.

Carrol S

Hurdle came from Marshall County, Missisippi. He studied

at Mississippi State University and was working before the war

in a sales roles. He died in November 1983 in his native

Marshall County. The American

Air Museum website also has a page dedicated to Sgt.

Hurdle however it too mentions that he spoke little about his

wartime experiences. Carroll Simpson (“Simpson”) Hurdle, oldest

child of Donny Oscar Hurdle and Cornelia Bell (Bull) Hurdle, was

born 7 October 1908 (Mississippi) and died 17 November 1983,

married Margaret Louise (“Louise”) Winter who was born 19 April

1915 (Holcomb, MS) and died 23 February 2008. Simpson and Louise

are buried in Slayden Cemetery (Marshall County, MS). They had

no children but are fondly remembered by relatives.

Carrol carried the MOS 612 which classified him as an Armourer

Gunner.

Bernard

Nitkin came from New Haven, Connecticut. He remained a

resident there until his death in 2011.

Bernard

Nitkin came from New Haven, Connecticut. He remained a

resident there until his death in 2011.

Bernard's life in public service was recorded in online Obituaries including this one at Legacy.com

Robert D

Shaver was another radar technician on B-17 42-97747. His

enlistment number unfortunately falls within a batch of numbers

not saved in historical US Army enlistment databases, however,

his name and serial were found on a shipping manifest of the

Queen Mary, dated July 11th, 1945 arriving in New York. At that

time he is listed as sailing with the 446th Bomb Group, but it

may have been a posting for the purposes of shipment. His

enlistment number starting with 3927xxxx suggested that he may

have come from California. It turns out he was Robert Dale

Shaver, from Manhatten, Kansas, who was working for the Douglas

Aircraft Corporation in Long Beach, California at the time of

his draft registration at the end of June 1942. Robert was

born in 1922 to Claude and Bertha Shaver. The local Kansas

newspapers in July 1945 reported that Sgt Robert or Bob

Shaver had returned from England.

Robert D

Shaver was another radar technician on B-17 42-97747. His

enlistment number unfortunately falls within a batch of numbers

not saved in historical US Army enlistment databases, however,

his name and serial were found on a shipping manifest of the

Queen Mary, dated July 11th, 1945 arriving in New York. At that

time he is listed as sailing with the 446th Bomb Group, but it

may have been a posting for the purposes of shipment. His

enlistment number starting with 3927xxxx suggested that he may

have come from California. It turns out he was Robert Dale

Shaver, from Manhatten, Kansas, who was working for the Douglas

Aircraft Corporation in Long Beach, California at the time of

his draft registration at the end of June 1942. Robert was

born in 1922 to Claude and Bertha Shaver. The local Kansas

newspapers in July 1945 reported that Sgt Robert or Bob

Shaver had returned from England.

Bob and his son very kindly collected by memories of the

incident and his wartime adventures. These are presented

below due to their extensive length. His posting to an

airfield near Ipswich ties in with the 446th Bomb Group being

based at

The aircraft, a Lockheed Vega built B-17G-30-VE, was one of the

famous wartime Flying Fortress bombers. It had been delivered

only in February 1944 and was enroute to Europe. The

presence on board of two radar technician passengers hints

towards the fact the aircraft was equiped with the then top

secret H2X bombing radar. This was also known as the

Mickey set or as the BTO, Bombing through Overcast unit.

Compiled by Dennis Burke, 2019, Dublin and Sligo. If

you have information on any of the people listed above, please

do contact me at dp_burke@yahoo.com

The testimony of Robert D

Shaver, prepared in April 2019.

WW2 Experiences - Robert Dale Shaver (39 274

851), 8th Air Force radar technician on a B-17 (42-97747)

that ran out of gas and ditched in the Atlantic at 49 Deg

46 Min N x 13 Deg 1 Min W off the coast of Ireland in May,

1944 - my story.

As a corporal just out of radar school in

Florida, the story of my trip to England to deliver a

specially outfitted B-17 Flying Fortress with the Air

Force's most top secret radar precision bomb site that I

now know they were trying to get to the front by D-Day is

something I have never forgotten. With the help of my son,

Joel, I will try to relate the story as I remember it, as

well as some general recollections from the war. In early

2019, Irish researcher Dennis Burke who had been

collecting accounts of that flight for

www.ww2irishaviation.com contacted me with details gleaned

from others and I am now able to fill in gaps in the

larger story I have wondered about ever since the events

transpired.

My name is Robert D. Shaver, a Kansan from

Wabaunsee County near Topeka. A guy came through town

looking for aircraft workers in California to support the

war. To get there, I hired on to drive a brand new Dodge

for an elderly couple that rode in the back seat. I was

working for Douglas in California building B-17s when I

joined the Army Air Corp at Ft. MacArthur in January 1943

at age 21. I took a troop train all the way across the

country to basic training at St. Petersburgh, Florida,

followed by Radio School at Truax Field in Wisconsin, and

then Radar Technician school around Boca Raton back in

Florida as part of the 8th Air Force. I reported to

Langley Field, Virginia where I got what they call a

delay-in-route so I could go back home to Tonganoxie on a

30 day leave then report back to Langley. Bernard Nitkin,

another radar technician, and I were assigned to support

the game-changing radar gear that would allow for

precision bombing through clouds and bad weather or in

total darkness in a specially modified B-17. I knew of

Bernard at radar school, but he was in a different class

and we didn't really meet until being assigned to the same

plane. The 9-person flight crew assigned to ferry the

plane over had flown together before, so Bernard and I

were there more as "passengers." Since the radar antenna

was substituted into the waist gunner bay, Bernard and I

took the place of two of the gunners who were to travel by

ship and we were being piloted by Lt. Clarence Fightmaster

and his men to England to deliver the aircraft in a hurry.

Before leaving, they gave us instructions on what to do if

ditching the airplane was required. There was the pilot

and co-pilot, bombardier and flight engineer, all on the

flight deck. Then five of us; the tail gunner, the radio

operator, the navigator, Bernard and I were in the radio

room.

We took off from Langley Field early one

morning headed for Goose Bay, Labrador. We got up to Maine

and lost a super-charger on one of the engines. We landed

and called back to Langley to get parts. That threw us

behind and we landed in Goose Bay about dark and just

ahead of a storm. We were socked in there for seems like

several days.

The radar we had on the plane was the most

secret thing in the Air Force. It could do precision

bombing through clouds or at night where normally you had

to be able to see the target visually. The radar antenna

gear could be cranked down in place where the waist

gunners normally sat, then there was like a TV screen

where we could see the ground to bomb. So we had to stand

24 hour guard on that plane the whole time we were there.

We weren't dressed for that and it was the most miserable

thing I've ever seen. There were four officers and five

enlisted men and the enlisted men had to take turns on

four hour shifts guarding that plane. I got acquainted

with a guy there at Goose Bay, I don't remember all the

details, but somehow I beat him out of a brand new

sheepskin flying suit. It fit me good and was the warmest

thing we had. We took turns wearing the suit on guard duty

to stand the cold. I stood the last watch so was wearing

the flight suit when we took off.

In a briefing we were told to take off and

climb to 11,000 feet where we were to break through the

clouds and then set a heading to Iceland. We ended up

having to go higher to get above the clouds and that threw

us way off. We called back to Goose Bay to request

permission to return but were told they were completely

socked in tight. Iceland was still open so we were to head

there. The pilot called back to Chris the navigator (we

called him Chris, not Gustav) that he needed a heading for

Iceland. The navigator had his sextant in a nice wooden

box he had to keep with him all the time. It had snowed

the night before leaving Goose Bay, and when we were

loading the plane, the box was dropped. Chris looked at it

when it happened and thought it was okay. He gave the

pilot a heading, but after a while the pilot asked him to

re-check the heading because something didn't seem right.

Then Chris checked and started cussing. The sextant was

damaged and no good to use. There we were not knowing

where we were and no navigation. We radioed someone, I

think in Greenland, and they said to go on to Iceland. We

asked how we were supposed to do that without navigation,

but headed on east. We did make brief radio contact with

Iceland but about that time the radio went out, and then

we didn't have any navigation or radio, and all we could

do is fly. The only thing we knew is that we were

ultimately headed to England. We were to be told our next

stop from Iceland, so all we knew was to fly east but we

didn't want to go too far to Finland where the Nazi's

would shoot us down. We threw everything out we could to

lighten the plane, and the pilot leaned it out to just

where we could stay going. We started flying south

(towards England, we hoped) but shortly after that the

pilot announced we were about out of gas. We talked about

whether we wanted to bail out or ride it down together,

and decided to stay together. We'd have been strung out

across a section of the North Atlantic and been almost

impossible to find if we had bailed out. They had told us

the temperature of the water was 26 degrees, and the

longest one could survive in that water was about 25

minutes.

We started doing our ditching procedure. I had

that heavy flying suit on, which was lucky. The first

thing we were to do is jettison the machine gun but we

couldn't get the mounting loose, so we sort of tied it off

to the side. We had assignments for what we were to do

before and after the plane hit the water. The five of us

in the radio room were to sit on the floor with our backs

to the forward bulkhead with the navigator and radio

operator to the front, then with their backs to them was

the tail gunner and Bernard with me in front of them all

so I was to be the first one up after we ditched. I was

the tallest one of the bunch and I was to stand up and

there was a lever right there to release the life rafts.

They were attached up high on either side. I was to go to

the left wing and hold the raft against the trailing edge

and the tail gunner was to go to the right. We hit the

water and I got up and the machine gun came loose and hit

me in the side of the head and knocked me down. We skipped

on the water and when we came back down there was water

coming in and I tried to get back up. The tail gunner used

me as a ladder to get out of there, but when I got to the

left wing the raft was clear back by the tail. I jumped

into the water to go back to get the raft but that heavy

flight suit started pulling me down. I had a Mae West on

and I pulled the chain and inflated it. That brought me

back up and I got the raft back to the trailing edge of

the wing and there stood the tail gunner. I said "What are

you doing here?" He said "Mine didn't come out!" So all of

us tried to get in the one life raft, but it wasn't big

enough. Bernard and I, I guess because we were

"passengers" and not part of the core crew, were off the

side in the water but Bernard started wailing and they

pulled him into the raft to shut him up.

There were supposed to be two paddles and some

rations and water in each raft but there was nothing. The

only thing was a patch kit in case we got machine gunned.

We were trying to get away from the airplane paddling with

our hands because we didn't know if the plane going down

would have a suction that could pull us under. There was a

cord attached to the plane keeping us from getting past

the wing tip. I tried to break the cord but couldn't.

Finally I wrapped the cord around my arms to get more

leverage. I said to Chris, "Grab my arms and break it!" He

said, "I’ll break your arms!" "Break it!" I said, and we

started snapping it and it finally broke. We had big

oxygen bottles in the plane tied together to some orange

plywood boards that all broke loose when we ditched.

I grabbed a board to be used as a paddle. We then

started counting noses and the bombardier and the flight

engineer were missing. We tried to decide whether to go

back to the airplane. We started hollering and looking for

them. The next thing we knew the front section came loose

at the main bulkhead and dropped down. Shortly after that

the right wing broke off and the left wing came up and

slipped out of sight. We thought they were gone. I

was still in the water and felt myself sort of slipping

away. Chris was right above me and was holding on to me. I

finally wrapped my arm through the rope around the top of

the raft and sort of hung there tied to the raft and

passed out.

It was about three and a half hours later when

I came to on the deck of this ship. It was a pretty small

ship, it seemed. I was stripped with one man rubbing each

leg and arm and a couple rubbing my body trying to warm me

up and rub life back into me. Finally I came to and said

"What the hell are you guys doing!" In a little bit they

wrapped me in blankets and took me into the cabin. It was

an Irish ship and the captain came in with two or three

fifths of whiskey under each arm. He said, "The good stuff

is all gone" as he poured out a big glass of whiskey for

each of us. We hadn't eaten for I don't know how many

hours. I drank it and it started warming me up. They came

around with another glass and I started getting warmer and

the room started spinning and I passed out. And, you know,

I came out of that without so much as a cold.

I got to looking around and there was the

bombardier and flight engineer. They were supposed to go

to the right wing then had seen there were too many people

on the left side so they dug the life raft out on the

right and took off. The ship found them first and they

told them about us and they started the search. I don't

remember knowing about it at the time, but stories from

those on the flight deck say the pilot saw the ship and

signaled to it before hitting the water. I am sure now

that cockpit decision was what allowed us all to survive.

The bombardier and flight engineer would have known the

ship was in the vicinity and must have headed right for

it. The pilot and co-pilot in our boat would have also

known, but I don't remember hearing about a ship being

near at the time.

I remember asking the captain how far it was

to land. "Two miles - straight down!" he said.

I don't think I really realized it at the

time, but we couldn't go to Ireland because they were

neutral and we could have been interned for the duration

if we set foot on their land. We just wanted to get to

England where we were headed, and the Irish ship was

already headed for England, so we sailed on in radio

silence. The ship was running short on food, and I

remember us having ham and eggs for just about every meal.

The German U-boats were supposed to be around

and the waters along Ireland and England had been mined to

keep them out. The ship was carrying a load of wine from

Portugal. To get around the U-boats, they had to make a

big loop and that's why they were up there where we came

down. The captain, using a map, had to make it through the

mine field and our crew spent time on the front of the

ship looking for mines, trying to get to the clear passage

nearer land. You could see them in the water and we even

scraped some. You have to hit them pretty good for them to

go off. We went along the west coast of Ireland and were

on the ship for I think several days. The ship's crew

treated us well. We would talk with them but we mostly

didn't have much to do.

They finally broke radio silence and called

the British because they didn't know if we might be German

spies trying to get into the country. We docked in

Fishguard, Wales and the British met us. They had us for a

week or two, questioning us separately time after time. We

finally convinced them who we were. Then they turned us

over to American intelligence and it didn't take them too

long to figure out who we were. We had lost everything but

the clothes we were wearing and our dog tags on the

airplane. I still had that flying suit and it had got the

side all torn up coming out of the airplane and we were

all a mangy looking bunch, out of uniform and getting

stopped by the MPs several times on the way to a base near

London. Since Bernard and I were not really part of the

flight crew, they put us into a little Quonset hut on the

base. They were trying to figure out what to do with us

with someone watching us all the time and all we could do

was go to the mess hall and come back. That went on for

several days. I finally got permission to talk to the

boss-man, he was a captain. I explained everything to him

and convinced him. He told me to go get Bernard and we

were supposed to report to somewhere else on the base.

They had us fill out our own service records to the best

of our recollections and you know, that thing followed me

back to the states and that’s still the only record they

ever had on me as far as I know.

We were first at Alconbury (482nd Bomb Group),

a base in the town Lord Haw-Haw (a.k.a. William Joyce -

American born but raised in Ireland) was from or well

known in. He was a traitor that went over to the German

side and would be on the radio like Axis Sally. He would

taunt us and say "You Yanks can't be on time; the clock in

the officers mess is 4 minutes slow" and we checked and it

was so he had eyes in the base. All the radar bomb site

planes we had were at that base and Lord Haw-Haw would

talk about how they were going to get them and us. You

could go into a pub in the town and if you mentioned his

name, they'd show they really hated him. We were there on

D-Day with the planes going over by the hundreds.

Since the Germans knew we had all those planes

at the same base, they decided to split them up and I

moved to a base at Ipswich with two of them and that was

right in Buzz Bomb Alley. Every evening the buzz bombs

would start and there were anti-aircraft guns blazing.

They told us they were manned by women. They would get a

lot of them but a lot of them got through. We'd see the

tracer rounds going and then they'd bring one down. We had

some fall in the vicinity but nothing right in the base.

I'm not sure the radar bomb sites were ever used much. We

Americans flew missions during the day, then the British

took over at night when it was safer from German fighters.

I don't remember many cloudy missions where the radar

bombing was needed, but two radar planes went out with

each bomb group, generally. I was ground crew for the

planes to check them out between missions. I was the only

one with a driver's license so I had to position all the

power units under the planes to do our system checks.

There wasn't all that much to do once I got to Ipswich

since there were only two planes to support.

I got a real nice bicycle so I could get

around away from the base. It was a deluxe model that

really turned the heads of the local boys. When it was

time to go back to the U.S. on the Queen Mary as war wound

down, I rode that bike to the dock. I knew I couldn't take

it with me, so there was this English boy that was really

admiring it. I said "How would you like to have this

bike?" "Gee, mister, my mom would whip me if I came home

with this thinking I stole it!" So I wrote him a little

note explaining the situation and put my name there. He

was so tickled with such a gift, especially after all the

sacrifice that was made by everyone during the war. I've

often wondered about how that boy with that bike made out.

On the way across the Atlantic, the ship got

hit by a big storm. All the gyros went out and the ship

was really rolling around. Almost everyone but me and a

friend got sick. When I got back to the States and was

getting off the Queen Mary, there were USO tents all along

the dock. Most of the guys were going over to get a belly

full of booze, but I grew up on a dairy farm and I had

really missed good non-powdered milk over in England. I

went to a tent with milk and drank it until I was about

sick.

After a 30 day leave, I reported to Clovis,

New Mexico and started training on a B-29 system for

Pacific duty, but the war ended before I got overseas

again. I was honorably discharged as a Sargent from Lowrey

Field in Colorado in October, 1945.

I took the train back home but my duffel bag

got lost. I went to the train depot in Tonganoxie about

every day "looking for it" but I was more wanting to see

Pattye in the office. A lot of jobs back then were being

filled by women since so many men had been away in the

service. I finally got her to go out with me and we

eventually got engaged. We got married and have been so

for the last 72 years, living in Wichita where we raised

two boys and I retired from Boeing after 32 years.

I am trying to find a picture of me in

uniform, but any that I had were left at my dad and

stepmother's house and have disappeared. My wedding

picture is attached and that is about as old a photo as I

have at this time. I am still trying to see if a photo can

be found in a WW2 museum or archive.

My son has pointed out that my account

differs from the official story in that I recall us having

some radio contact after Goose Bay and in us having a

sextant but it was ruined. It was a long time ago, so

recollections can be tricky. I only offer this account as

my side as I remember it, and hope it serves to illuminate

history in some way. These memories seem very clear to me

and I even still have nightmares about that plane trip and

my time in the water.

ww2irishaviation.com is kindly hosted by Kinsalenets.com ![]()