AW Whitley, Co. Donegal, January 1941.

The 23rd January 1941 would see the arrival in Ireland of two lost Royal Air Force Aircraft. One, Hudson P5123, its story told here, resulted in four safely interned airmen and a damaged aircraft later purchased by the Irish government.

The other arrival brought with it a much more tragic result.

On that day, Irish Coast Watching Service observers, Gardai and

other witnesses recorded the transit of an aircraft up the west

of Ireland, then passing eastward past Malin Head, before

returning and circling around Limavady airfield, its homebase in

Northern Ireland.

A crew member, a Sergeant Jefferson, was found in the vicinity

of Quigley's Point and taken into custody by the Gardai there.

The map below, screen grabbed from Google Maps, shows the

general location of the place names mentioned below. The

exact location of the aircraft crash is not known by this writer

at this time but it is thought it may be in the area under the

text "Glenard townland" on the map, there are two low peaks

shown on old ordnance survey maps as Glenard West, 397 foot, and

Glenard East, 547 feet. Irish Army reports at the time

place the crash location as Cockaveny

but given the proximity to Glanard, this must be the

townland of Crockahenny.

The term 'Glenard Hill' seems largely to have come into use only

in relation to publications on this crash. The photos of

the excavation on the crash site in 1990, see details below,

indicate that it was in a wooded area. Those would appear

to be managed forests planted well after the end of the war.

The Squadron Diary for 502 Squadron RAF covers the loss of this

crew with scant detail. In the Form 541, record of Work

Done, it states simply: Search

for tugs seeking bombed ships. crashed off Quigley Point

Lough Foyle at about 2130

Their take off time is given as 0923

and expected time of return as 2330.

A form 765 investigation report was raised and filed by 502 Squadron on this occasion. Sadly the original file copy in UK National Archives, within Casualty File AIR81/4935, is damaged so the end of the conclusions cannot be read. The findings of the investigation were summarized as follows in the remarks of the unit commander:

Diagnosis of primary cause of accident

or forced landing:

The navigator was lost, the aircraft

ran short of petrol and had to be abandoned by crew.

Diagnosis of secondary cause of

accident or forced landing.

If the aircraft has got seriously

off its intended position during a patrol it is entirely

dependent on W/T D.F. for homing to its base, particularly

in bad weather. The D.F. facilities at Limavady are

unsatisfactory and in this case apparently the aircraft

wireless set was serviceable. The weather conditions

were bad.

General remarks:

It is suggested that a court of

inquiry should investigate the crash. The cause

appears to have been inadequate navigation and a failure of

the wireless equipment, The aircraft had been out of

sight of land for several hours and in this time, with quite

good navigation the aircraft could have been so far out of

position on its return that only W/T [illegible] facilities could ensure a safe return

[The remainder of the remarks cannot be read from this copy]

The loss of of this Whitley from 502 Squadron was the first of

three losses from the Squadron in 1941 that involved Squadron

members ending up in neutral Ireland, the others being the loss

of Whitley P5045 on the 11 March and

the abandoning of Whitley Z6553 on the 30 April.

F/O Leslie John WARD 41501 was

born in April 1918 in New Westminister, British Colombia to

Elizabeth and Luke Ward

F/O Leslie John WARD 41501 was

born in April 1918 in New Westminister, British Colombia to

Elizabeth and Luke Ward

He joined the RAF on the 6th of Oct 1938, having sailed to the

UK it seems in August.

Leslie Ward was posted into 502 Squadron during April 1940 from

No 3 Coastal Patrol Flight. His first operational mission

appears to have been on the 17th of May with Sqn/Ldr Corry from

RAF Hooten Park where the Squadron had a detachment of Anson

aircraft.

His internment was widely reported in Canadian newspapers in

january 1941, including the following in the The Vancouver Sun

on January 30th:

Vancouver Flier

Interned in Eire

Love of adventure has led Flying Officer Leslie

John Ward, 22, from the University of .British

Columbia to an internment camp in Eire.

Flying Officer Ward, whose mother lives

at 2401 East Thirty-eighth Avenue, has been

interned in the Irish Free State as the

result of a flying accident, the Air Ministry

notified Mrs. Ward.

He left Vancouver in August 1938 to work his

passage to England so that he could

join the RAF. Last year he graduated

as a flying officer and was posted to the Ulster Air

Command at Belfast.

Last July Flying Officer Ward married an

English girl whom he had met while a student

pilot.

His plane crashed in County Donegal last week

and the only word received since by his

mother is that he is safe and interned

in Eire.

Newspapers in August 1941 carried the exciting news of his

participation in a failed escape attempt on the night of June

25th. He had written to his mother describing the attempt.

His family kindly provided a copy of is memoir of the

landing. In this he recalled:

"About 4 a.m. on the night of 23/24 Jan

41, I was roused from bed by a telephone call-out from the

Limavady Ops room. By standing arrangement, I picked

up my co-pilot, Plt Off Johnson, in the old Morris and we

made our way to the airfield. Johnnie was also married and

lived in digs. The rest of the crew, navigator Sgt

Hogg, two wireless operator/gunners, Sgts Jefferson and

Green, were at the airfield on our arrival. Sgt Hogg

was a stand-in as my regular navigator - a pilot officer

whose name completely escapes me; we had not been together

long - had contracted measles and had been out of action for

weeks. He was a very pleasant and competent chap and

had the remarkable record of having completed a bomber tour

of 42 trips in 6 weeks. He went to one or other of the

Channel ports in a Fairey Battle to bomb the assembling

invasion barges every night over the period. Now he

was lucky to get measles.

At the Ops room, we were told that three

ships had been torpedoed off the west of Ireland – about

15/16º W if I remember aright. They were fairly far

apart and we were to stand by in case a Sunderland flying

boat could not take off from Pembroke Dock, as the weather

was very bad. For some 4 hours, we hung about; the

trip being on and off, our weather was pretty poor

also. Eventually, the Sunderland was scrubbed and we

got away at about 8 a.m. We flew by dead reckoning

navigation to each of the reported positions of the stricken

ships, or now of their lifeboats, if any. The weather

was rough; we were flying in the region of a couple of

weather fronts with the consequent wind shifts. We had

to fly low to keep under cloud for visual search and this

did not aid navigation as we could not make use of W/T MF

triangulation for position fixing, for what this facility

was worth. So the accuracy of our navigation had to be

very doubtful when the target was a lifeboat or two in a

wild ocean. Anyway, we saw nothing after flying to

each of the given positions and back to the first. We

were then faced with a decision: if we returned to base from

where we were, we would arrive back with flying time in

hand, not a thing to do when there could be seamen in peril

and whom we might yet find. On the other hand, if we

searched once more another of the positions, we would have

enough fuel, but things would be pretty tight. We

decided to stay with it, continued with the search and then

set course for base. We made landfall on the west

coast of Ireland at what we identified as the Aran Islands

(Inishmore, Inishmaan and Inisheer) at the entrance to

Galway Bay. This bay is about 53º N and we had aimed

at about 55º 30’ N, i.e. Tory Island on the NW tip of

Ireland. So we were some 150 nautical miles adrift –

heaven knows where we had been during the day. There

were two courses of action to consider: (1) to ignore Eire’s

neutrality and make a beeline for Limavady or Aldergrove;

(2) to fly around the coast to Lough Foyle and

Limavady. Course (1) was attractive as it would ease

our fuel problem, but we would have to climb above cloud,

because of the intervening terrain, and descent at the other

end would call for R/T or W/T contact for an accurate let

down. There was none with Limavady, but there was with

Aldergrove. But the decision was made for us, the

W/Ops reporting that our wireless equipment was out of

action. So we set off around the coast to Limavady.

Our flight north went smoothly

enough, darkness came, but we reached Tory Island,

recognised by its lighthouse. We were practiced in

reading the lighthouse coding of flashes and occults as

marked on our charts. From Tory Island, we made our

way 35 miles to Inishtrahull lighthouse off Malin Head and

then on some 20 miles to Inishowen lighthouse at the mouth

of Lough Foyle. We were very low on fuel, but with

only 7 or 8 miles to go, we felt we had made it. We

made a timed run from Inishowen lighthouse but could not

pick up the airfield in the weather prevailing and we were

very mindful of Ben Twitch, which made searching about low

level a dodgy pastime. We made several runs but with

no luck. I was told later that a destroyer in Lough

Foyle had aimed a searchlight at the airfield to guide us,

but we did not see that. With the fuel state

desperate, we had been in the air for nearly 11 hours, I had

to make a decision and this was to climb to about 4000 ft

and head in a south-easterly direction over land for a

spell, turn about and bale out. I had the crew don

their parachutes and line up by the escape hatch – a trap

door in the floor, forward of and a couple of steps lower

than the pilot’s position. My co-pilot was in the lead

with the brief to try and determine that we were over land,

then go, with the other three following at once. After

what seemed an age, the bale out was made. The last

man, Sgt Jefferson, was very slow in following on and this,

as it happened, saved his life. With the crew gone, I

tried to fit my parachute to my harness; they were of the

chest type. I found that I couldn’t do this and get my

arms around it to the control column. I therefore had

to leave my seat and stand in the well, trying to fly the

aircraft with one hand at head level and fighting with the

parachute fitting with the other. I was not

happy. At last, I got the parachute on, noted that I

was at about 200 ft, knocked the ignition switches off

(hindsight says I shouldn’t have done that) rushed to the

trap door, got my head and shoulders through and found to my

horror that my jacket was caught up on something and out I

could not go. Panic in the first degree. I

backed into the aircraft, rushed back to the cockpit and

tried to pull the aircraft out of the dive it was in.

There was no chance standing in the well and heaving at head

level. I saw the aircraft was passing through 1000 ft

and then all my panic buttons were pushed and I believe I

outstripped anything the Bionic Man or whoever could

achieve. I swear that I dived at that trap door hole

from about 6 ft and went through without touching the

edges. I pulled the rip cord at once, saw the ground

(snow covered), saw the aircraft go in with hardly a sound

(it had about 4000 lb of bombs on board and so the silence

was appreciated) had time to note that I was swinging in the

parachute like mad from side to side across my line of

progress which was backward. Before I could do

anything about anything, I hit the deck and the next ½ hour

or so is a mystery to me.

Our flight north went smoothly

enough, darkness came, but we reached Tory Island,

recognised by its lighthouse. We were practiced in

reading the lighthouse coding of flashes and occults as

marked on our charts. From Tory Island, we made our

way 35 miles to Inishtrahull lighthouse off Malin Head and

then on some 20 miles to Inishowen lighthouse at the mouth

of Lough Foyle. We were very low on fuel, but with

only 7 or 8 miles to go, we felt we had made it. We

made a timed run from Inishowen lighthouse but could not

pick up the airfield in the weather prevailing and we were

very mindful of Ben Twitch, which made searching about low

level a dodgy pastime. We made several runs but with

no luck. I was told later that a destroyer in Lough

Foyle had aimed a searchlight at the airfield to guide us,

but we did not see that. With the fuel state

desperate, we had been in the air for nearly 11 hours, I had

to make a decision and this was to climb to about 4000 ft

and head in a south-easterly direction over land for a

spell, turn about and bale out. I had the crew don

their parachutes and line up by the escape hatch – a trap

door in the floor, forward of and a couple of steps lower

than the pilot’s position. My co-pilot was in the lead

with the brief to try and determine that we were over land,

then go, with the other three following at once. After

what seemed an age, the bale out was made. The last

man, Sgt Jefferson, was very slow in following on and this,

as it happened, saved his life. With the crew gone, I

tried to fit my parachute to my harness; they were of the

chest type. I found that I couldn’t do this and get my

arms around it to the control column. I therefore had

to leave my seat and stand in the well, trying to fly the

aircraft with one hand at head level and fighting with the

parachute fitting with the other. I was not

happy. At last, I got the parachute on, noted that I

was at about 200 ft, knocked the ignition switches off

(hindsight says I shouldn’t have done that) rushed to the

trap door, got my head and shoulders through and found to my

horror that my jacket was caught up on something and out I

could not go. Panic in the first degree. I

backed into the aircraft, rushed back to the cockpit and

tried to pull the aircraft out of the dive it was in.

There was no chance standing in the well and heaving at head

level. I saw the aircraft was passing through 1000 ft

and then all my panic buttons were pushed and I believe I

outstripped anything the Bionic Man or whoever could

achieve. I swear that I dived at that trap door hole

from about 6 ft and went through without touching the

edges. I pulled the rip cord at once, saw the ground

(snow covered), saw the aircraft go in with hardly a sound

(it had about 4000 lb of bombs on board and so the silence

was appreciated) had time to note that I was swinging in the

parachute like mad from side to side across my line of

progress which was backward. Before I could do

anything about anything, I hit the deck and the next ½ hour

or so is a mystery to me.

I awoke to find myself flat on my back

with the parachute cords leaving me in a straight line from

my chest, between my legs to my parachute 20 ft away.

I recall vividly lying there wondering if I was intact and

trying each limb in turn and then sitting up. All

seemed well. But I saw people in little groups walking

towards the bits of my aircraft, mainly the tail unit that

was sticking up in the air and lit by fragments that were

burning. The aircraft had plunged into a bog near

Buncrana, on the eastern side of Lough Swilly, the fjord

west of Lough Foyle. Hence the silent crash and other

blessings. I made a rapid appreciation of the

situation that would have done credit to Field Marshal

Montgomery and decided that my best bet was to head on a

slightly roundabout path in the direction from which the

sightseers were coming to try by some means to establish

where I was – mainly on which side of the border I

was. How I was going to know that I have no notion now

but it seemed a good idea at the time. I had made my

way a couple of hundred yards when I came to a stream.

Fearlessly, I crossed this despite it being about 6 inches

deep. As I stepped out on the far shore, some 5 ft

away I bumped into a man and his young son who had come to

see what was cooking. Politely he said goodnight (you

must appreciate that the Irish all make greetings a step

ahead – like good morning at night and good afternoon in the

morning) and I put to him the question topmost in my mind

such as Ulster or Eire. He said Eire, so I said good

night really meaning goodbye. However, he said not to

worry but to follow him and he would see me right.

Rather the converse of take me to your leader. He took

me to a cottage in which there was a woman and a young girl

and an open peat fire. I was offered a chair at a

table and a cup of tea and a couple of boiled eggs, if I so

wished. Then people began to arrive, mainly women and

children, who said nothing but stared at me, nothing hostile

but rather disconcerting. Very soon a man arrived who

sat opposite me at the table silently, whilst covering me

with an enormous revolver. I then realised that the

boy I had met at the stream was missing. The word had

been got out. After a time a very affable police

superintendent arrived, told me not to worry, for I would be

over the border in the morning. He had pushed many a

drunken sailor over the bridge at Londonderry, he said, when

they had lost their way. I was taken by him under

escort to a police station, I believe at Buncrana, where I

was again assured that my return over the border was

certain. Soon some Irish Army officers arrived and

said they were to take me to the local Army HQ but not to

worry, etc., etc. I cannot recall where the HQ was but

think it was in the Lough Swilly Hotel, near Londonderry,

but on the Eire side of course. I was shown to a

bedroom and invited to take my rest. I was very tired

and it was now evident that I had done some damage to one

knee – can’t remember which one now, and the prospect of a

lie down was welcome but the bed linen was filthy – I do not

exaggerate when I say it was black. The clothes were

turned back and there was the pit left by the last

occupant. As I was to become accustomed to later, the

Irish Army bed sheets were real linen, right enough, but of

the weight of sail canvas! I had just taken off my

flying jacket and flying boots and preparing to lie on top

of the bed when a Royal Navy Commander was announced.

He was in uniform, but hatless, and wearing a Navy

mackintosh which, in those days did not bear badges of rank

(nor did those of the RAF) – so was “incognito”. He

had come to find out what we found out in the Atlantic, if

anything. I had nothing for him, of course. As

he left, he told me not to worry about my position as it was

certain I would be over the border in the morning.

Later on, I was told by Elizabeth that members of the

Squadron had formed a party to dash across the border by car

and rescue me, but were having difficulty in finding out

where I was from moment to moment and were eventually told

not to bother as I was being sent back in the morning.

The next day, I was told by the Army

that there were certain formalities to be gone through

before I was returned and we were to go to Army HQ at

Athlone. By this time, I was joined by my wireless

operator, Sgt Jefferson, and we set off in a car to

Athlone. There we were told that there was a change

and we were to go to Command HQ at The Curragh in

Kildare. So Jefferson and I and our officer escort

took lunch and then bundled into the car again and set

off. We arrived at The Curragh in the evening and were

taken to the Officers’ Mess where we were met by the Camp

Commandant, Colonel McNally. He was very friendly,

told us not to worry – all would be well. We were fed

on sandwiches and drinks and then told that we had better

get to our rooms and get some rest. We were taken

about a mile to a hutted camp surrounded by a high barbed

wire fence. The gates were opened, we went in, the

gates were shut and locked and we were interned –

prisoners. This we found out when we went into one of

the huts to be greeted by a batch of 6 RAF aircrew, who

quickly put us in the picture. Four of them had

arrived in the Camp only hours before us and, in fact, crash

landed on the shores of Galway Bay at the very time we were

sniffing around the Aran Islands as mentioned earlier.

So ended that particular chapter of events and I was not

happy."

He was one of the Allied internees that was released on the 18th

of October 1943. He filed an escape and evasion report

upon his return to the UK that week. The reports reads as

follows but strangely he is quoted as saying his flight occurred

on 24 Nov 1940. The date of his interview was 20 October

1943 and the file was signed off by the reporting officer on 2

December of that year. It is possible that the details of

the date were confused during that time:

1. Internment

I was captain of a Whitley aircraft which left LIMAVADY

on 24 Nov 40 on an operational flight. Owing to bad

visibility and shortage of petrol, we were compelled to bale

out in County DERRY in the neighborhood of LOUGH

SWILLY. Three members of the crew were drowned.

The other members of the crew were:-

Sgt. G. V. JEFFERSON, Wireless Operator

P/O. E.I.C. JOHNSON )

Sgt. W. HOGG

) drowned

Sgt. J GREENWOOD )

Both JEFFERSON and I were arrested shortly after

landing by the local security police. We were taken to

THE CURRAGH Camp on 26 Nov.

2. Attempted escapes

(a) On 25 Jun 41 I was one of the nine who escaped,

but was recaptured.

(b) In Feb 42 I took part in the mass ladder escape,

but did not get over the wire. I was not in the camp

at the time of the mass attempted escape on 3 Aug 42.

For much of the time he was interned in The Curragh he was the

highest ranking Allied officer, and was thus the Officer

Commanding of the internees group. The

He returned to active service with the RAF and was posted to

102 Squadron in July 1944, where he was awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross. His mission with 102 Squadron

was on the 1st August to a target in France but the mission was

ordered to be abandoned by the master bomber. The award was

published in the London Gazette on the 16 February 1945.

He remained in the RAF post war, being promoted to Squadron

Leader in 1947 and lived out his days in the United

Kingdom. He was further promoted to Wing Commander in

1954. He passed away aged 76 in June 1994 in Shropshire

P/O

Edward Ian Croucher JOHNSON 41931 was a young Royal Air

Force Pilot, born in Tunbridge Wells in January 1917. His

mothers name is unknown but his father is recorded as an Edward

Johnson from Rushfer, Sussex. A note in the 24 year old

officer's casualty file points out that that his father was "not

to be informed".

P/O

Edward Ian Croucher JOHNSON 41931 was a young Royal Air

Force Pilot, born in Tunbridge Wells in January 1917. His

mothers name is unknown but his father is recorded as an Edward

Johnson from Rushfer, Sussex. A note in the 24 year old

officer's casualty file points out that that his father was "not

to be informed".

He had been married only eight short months previously, on June

1st, to Lois Meade Newton from Antrim, the daughter of an RAF

officer, Thomas Meade Bertram Newton. The wedding had

taken place in Antrim Parish Church. The young couple

would have to deal with the tragic death of F/Lt T M B Newton of

14 Flying Training School at Cranfield on the 23 October 1940

aged 44. Lois, his widow, living in Rickmansworth,

Hertfordshire in the immediate aftermath of his death.

The officers body was found washed up on the shores of Lough

Foyle in the townland of Ballyrattan on the 25th of January

1941. His death certificate issued by the local registrar

records his name as Edward I C Johnstone of Aldergrove, Co

Antrim. P/O Johnson's remains were returned to England and

were buried in Rickmansworth (Chorleywood Road) Cemetery.

It was finally in late 2023 that is was discovered that Lois

had re-married post war to a gentleman name Ernest De Boos, and

that she had lived to the grand age of 101, passing away only in

July of 2022. Ian, as he was referred to by his family,

was mentioned in her obituary and had never been

forgotten. Lois and Ian's daughter was born the summer

after his death and his grand children and great grand children

fondly remember his sacrifice.

Sgt

James Edgar HOGG 969800 was the son of Barbara A Hogg from

Cheadle Heath, Stockport. Most wartime records and indeed

her own letters to the RAF highlight that James was her adopted

son. The 1939 register finds James and Barbara residing at

their home in Stockport. Barbara was a Public School

Headteacher and James is listed as a student, awaiting

mobilization from RAF.

Sgt

James Edgar HOGG 969800 was the son of Barbara A Hogg from

Cheadle Heath, Stockport. Most wartime records and indeed

her own letters to the RAF highlight that James was her adopted

son. The 1939 register finds James and Barbara residing at

their home in Stockport. Barbara was a Public School

Headteacher and James is listed as a student, awaiting

mobilization from RAF.

He had been born in South Shields on the 8 of July 1918

It is clear from the AIR81 files that Barbara Hogg corresponded

with the other members of the crew and the family of Sgt

Greenwood. She wrote to the RAF in March 1943 requesting

details of how to contact the two surviving crew members.

A letter of reply dated the 29 April 1943 directed her to write

to F/O Ward and Sgt Jefferson at the the Curragh Camp, Co.

Kildare, Eire. She was also given the names of P/O Johnson

and Sgt Greenwood. She also wrote at that time to their

former Squadron commander, W/Cdr R Terrance Corry.

Some months later, she forwarded letters of condolence to the

families of Sgt Greenwood and P/O Johnson via the Air Ministry.

Sgt George Victor JEFFERSON 816145

was the only Allied internee during the war to hail from

Northern Ireland.

Sgt George Victor JEFFERSON 816145

was the only Allied internee during the war to hail from

Northern Ireland.

George was born on the 11 Nov 1920 to George and Margaret

Jefferson. He lived at No. 97 University Avenue in

Belfast. He had enlisted in the RAF in January 1939

He was released in October 1943 along with F/Lt Ward and other

internees. By this time he had been promoted to the rank

of Warrant Officer. It is not known at this time if he

returned to operational flying.

He passed away in July 2008 in Belfast.

The daughters of another British internee, Robert Harkell, were

able to provide the following group photo of some of the British

internees. The three men standing at the rear of the photo

in civilian attire were local civilians. Those faces that

can be identified are believed to be:

In the front row of the photo, from left to right

Sgt Robert George HARKELL 749495

Sgt Norman Vyner TODD 551678

Sgt William BARNETT 973926

Sgt David SUTHERLAND 51946

It seems most likely that the tall man standing at the very left

of the photo is Sgt Herbert Wain RICKETTS 581473.

The airman with the light coloured hair standing at the middle

is Sgt George Victor JEFFERSON 816145

Another photo from the family of internee S J Hobbs included

both Denys Welply and Norman Todd.

It is not known when the image below was taken exactly, but it

includes both Sgt Hobbs and F/Lt Proctor so is likely to have

been around the time of Sydney Hobbs wedding, though the lady in

the photo does not appear to be his wife Joan. This small

and battered photo shows the following Royal Air Force

internees:

Standing, Left to Right: Herbert Wain RICKETTS, Denys

Welply, David SUTHERLAND, Douglas Victor NEWPORT, Leslie John

WARD, Robert George HARKELL, William Allan PROCTOR, George

Victor JEFFERSON and Aubrey Richard COVINGTON.

Kneeling, Left to Right: Norman Vyner TODD, Sydney John

HOBBS.

Sgt Lewis GREENWOOD 553918 was born to

Samuel and Mary Agnes Greenwood, of Halifax, Yorkshire in March

1922. He doesn't appear listed with his parents in the

1939 register and there are no other siblings residing with

them.

Sgt Lewis GREENWOOD 553918 was born to

Samuel and Mary Agnes Greenwood, of Halifax, Yorkshire in March

1922. He doesn't appear listed with his parents in the

1939 register and there are no other siblings residing with

them.

Lewis had infact enlisted back in May of 1939. He was

first trained as a ground based wireless operator in mid 1939

but seems to have spent much of the winter of 1939 and spring of

1940 possibly in hospital per his redacted service record.

He was posted to 102 Squadron in May 1940 where he was selected

for Air Crew training in July. He was sent to 8 Bombing and

Gunnery School in August for a months training, then on to 1

Coastal Operational Training Unit the following month and

arrived at 502 Squadron on or around the 20th of October 1940.

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer of September 2nd,

1941, published a note that Lewis Greenwood (19), R.A.F., only

son of Mr and Mrs Greenwood, St Augustine's Terrace, Halifax -

had previously been reported missing, but was now officially

stated presumed killed.

His name was recorded in the "Calderdale War Dead, A

biographical Index of the War Memorials of Calderdale" as: 76 St Augustine's Tee, Hx. Educ Warley

Council Sch. Worked for Hellowells,

Delph St Metalworks.

Enlisted at 17 No 553918

While no trace was ever found of Sgt.s Hogg and Greenwood, a

lifevest was washed up on the same shore Johnson was found, they

day after his body was recovered. The details of the

markings on the vest were recorded and on to the british

reporentative in Dublin, and from there to the Air Ministry.

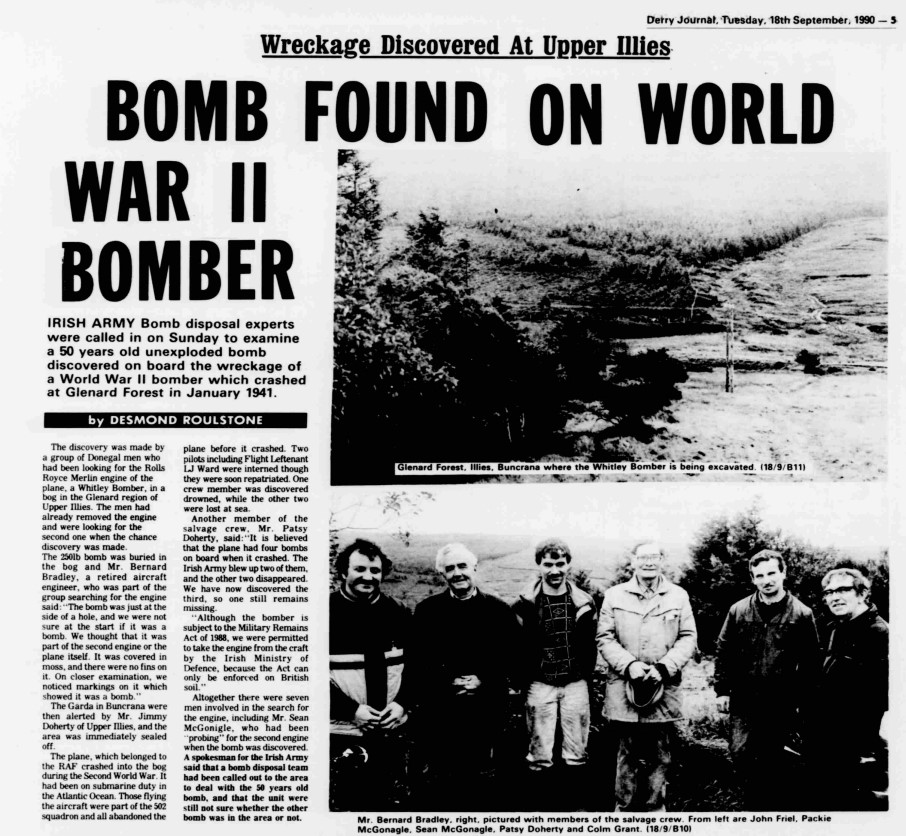

The wreckage of the stricken bomber had buried itself in the boggy hill side. And there it lay until some local men undertook to excavate the crash site in September 1990. This effort is described by John Quinn in his 1999 book, "Down in a Free State". The dig revealed an engine, a landing gear leg and other pieces of wreckage. It also revealed an unexploded bomb! While the Irish Army report from 1941 had stated that all ordnance had been dealt with, one of the aircraft's bombs eluded the Irish Army. The Irish Army of 1990 had to be called in once again and they made the device safe. This story made the newspapers in Ireland.

It is not known what became of the excavated wreckage.

Compiled by Dennis Burke, 2026.